Big Data: Past, present, and future perspectives from an integrated delivery system

View Dr. Larson's AHCJ conference slides. (PDF, 608 KB)

Dr. Eric Larson prepared these reflections on Big Data and Group Health for the Association of Health Care Journalists conference in Santa Clara, Calif., on April 24, 2015.

Big Data means information that’s broad and deep: about many people, with many measurements per person, or both. Integrated care systems like Group Health have had Big Data for decades. And we’ve learned a lot about how to avoid problems and get the most benefit from the great research opportunities of Big Data.

We’ve found that most patients are enthusiastic about sharing their information—but have some concerns. Although it can streamline research, in and of itself, Big Data can’t improve care or health. And because it can be fast, Big Data research may be particularly prone to sensationalist claims and misleading reports.

What do we mean by Big Data?

Big data means structured (and unstructured) information from various sources: patients, electronic medical records (EMRs), medical charts (including using natural language processing), administrative claims, tests and results, and self-reported and self-collected data.

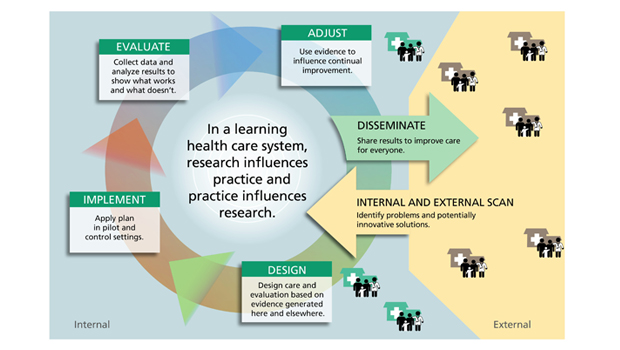

As a pioneering not-for-profit integrated health care system, Group Health has Big Data on a stable population since the mid-1970s, when it computerized prescription refills, lab tests, and diagnoses. Well before the U.K.’s National Health Service, for instance, we had ready access to “complete” capture of vast amounts of information on the health care and health of a representative population. This attracted outside researchers—and eventually led to an embedded research operation: now called the Group Health Research Institute (GHRI). We’ve had an amazing track record of advances and innovations—leading to the aspirational concept of the learning health care system, our vision for how we can use Big Data for ongoing efforts to achieve the “triple aim” of improving the care experience, population health, and health costs.

A cautionary tale

An early lesson from before my time at Group Health illustrates how Big Data can be misleading. In 1981, the Boston Collaborative Drug Study used Group Health data to conclude that using spermicide could lead to birth defects and spontaneous abortion. The birth defect outcome is quite uncommon. Group Health doctor Richard N. Watkins, MD, reviewed charts of babies with birth defects and found that several babies in that data set were from planned pregnancies—they weren’t actually exposed to spermicides, even though their mothers had been given them. In 1986, Dr. Watkins published his findings in a JAMA letter. Then in 1987, the New England Journal of Medicine published more papers refuting the earlier finding.

Based on examples like this and other such experiences around the country: Familiarity with the actual information contained in Big Data and local practice can be critical to avoid mistaken conclusions in research.

Local control, global impact

Years ago, four integrated care systems including Group Health explored how best to share information in projects like the National Cancer Institute’s HMO Cancer Research Network (HMORN) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Vaccine Safety Datalink. We eventually settled on a “federated” data model, instead of a centralized model. So in the Virtual Data Warehouse (VDW), which the HMORN uses, information stays housed in individual systems, but programmers can use common programs to extract “de-identified” data without information that could potentially identify people. Networks can also work together to look for opportunities to standardize how they store data in their system.

Now GHRI is involved in many national (and international) collaborations that combine Big Data to achieve more diversity and statistical power to answer pressing questions definitively. Just a few examples:

- HMORN: A growing number of researchers embedded in 20 health systems combine information on a diverse population of more than 15 million people;

- National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI);

- FDA’s Sentinel Initiative: a rapid-response electronic safety-surveillance system that monitors drugs, devices, and vaccines in 120 million people;

- Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network: National Human Genome Research Institute project with 10 participating teams, linking genomic data from existing biobanks to EMR data to discover genetic causes of disease, using a combined VDW approach with standardized download of data to a public Big Data repository.

Patients’ perspectives

“Routinely collected data provide great potential for extracting useful knowledge to achieve the triple aim in health care,” according to the Institute of Medicine’s 2013 Clinical Effectiveness Research Innovation Collaborative report. We agree. See “How Big Data Can Lead to Safer Drugs and Vaccines” about the work of GHRI’s Jennifer Nelson, PhD.

But how do patients feel about this?

We’ve found that trust matters. And local control (as with the VDW), personal relationships, and patient engagement help to build trust in using routine health care records data. We must address cultural and ethical problems to:

- Engage patients and protect their privacy;

- Acknowledge the need for individual institutions to maintain some control over data;

- Develop oversight policies and practices that eliminate barriers to sharing information and prevent losing precious opportunities to improve care and save lives; and

- Give moral consideration to harm when clinicians lack information needed to determine which approaches work best.

“Consider how the consent process could foster respectful engagement rather than merely mitigate risk,” we wrote in Science in 2011.

The promise of Big Data: quick, but not dirty

More use of EMRs provides data that’s abundant, inexpensive, less biased—from diverse people, treatments, and outcomes. Big Data has the potential to lead to better, faster:

- access to evidence for use in clinical decision making;

- public health surveillance, like detecting and managing epidemics such as E. coli outbreaks and flu pandemics;

- ability to target services like cancer screening and routine monitoring of patients with chronic illnesses to specific populations; and

- patient safety with fewer medical errors (e.g., Vioxx).

Efficient use of data can speed discovery and translation. Studies that once required decades of data collection can now be accomplished in just months. The FDA’s Sentinel uses vast amounts of data to look quickly and efficiently at post-marketing drug safety. And NIH’s Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory is rapidly conducting pragmatic clinical trials.

In efforts like these, lines are blurring between safety and quality improvement and traditional clinical research. In these instances, teams are discovering that research oversight can be overly burdensome and actually obstructive to achieving routine clinical improvement. I proposed a way to address this problem, which is admittedly very complex, in JAMA in 2013.

But Big Data doesn't necessarily improve health and health care

Big Data must be transformed into usable, actionable information that can be used to improve health—and health care’s quality and safety. Clinicians need 24/7 decision support based on high-quality, generalizable science from representative populations. Patients and the public will also increasingly have that decision support directly at hand. The process will involve shared decision making and support behavior changes. But how will we distinguish responsible decision support providers from vast amount of bogus material in cyberspace today?

Big Data and the Internet have tremendous persuasive power—and may be extra prone to misleading reports. It’s hard to create proper perspective about statistical risk, personal risk, and context. There is way too much self-promotion of advice and products—from private and public (including academic) sectors. Overdiagnosis, overtreatment, and medicalization of everyday life constitute a huge threat.

Honest brokers are needed, so quick Big Data don’t lead to quick and dirty hype.

Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, MACP.