Bariatric surgery may have ‘legacy effect’ on diabetes complications

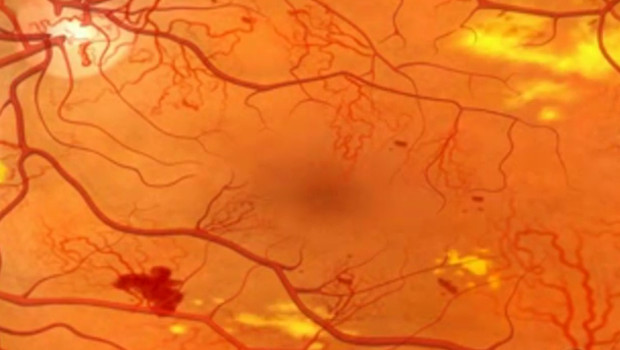

A close-up view of an eye with diabetic retinopathy.

Dr. Arterburn linked even short-term diabetes remission to less risk for microvascular kidney, eye, and limb diseases

by David Arterburn, MD, MPH, a Group Health Physician and senior investigator at Group Health Research Institute (GHRI)

Uncontrolled diabetes is known to lead to complications including microvascular diseases of the kidneys (nephropathy), eyes (retinopathy), and nerves (neuropathy)—as well as macrovascular ones like heart attacks and strokes. After bariatric surgery, type 2 diabetes goes into remission in most people who had the disease, according to many prior studies, including our own. However, we also know that people who are at an early stage of their diabetes are most likely to enter into remission. Along with that remission, we have now shown that their risk for diabetic nephropathy may decline.

Just as some people can at least partially regain weight lost with bariatric surgery, so too their diabetes may eventually relapse, although the mechanisms of weight regain and diabetes relapse are likely to be different. Those who relapse are more often those who have had diabetes longer, are requiring insulin, and have poor blood sugar control. But my colleagues and I wondered whether people who relapsed their diabetes would still have better long-term health outcomes that those who never remitted their diabetes. So we designed a study to address two questions:

- Does transient post-surgery relapse of type 2 diabetes have a “legacy effect” (a.k.a. “metabolic memory”), conferring lasting protection against developing microvascular diseases?

- Does the degree of that protection depend on how long a person spends in remission before relapse?

Yes, and yes

That’s just what we found, in the largest multisite study of this issue to date. We published “Long-Term Microvascular Disease Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes After Bariatric Surgery: Evidence for the Legacy Effect of Surgery” in Diabetes Care.

Prior studies had shown a “legacy effect” where transient periods of improved control of type 2 diabetes without surgery lowered the long-term risk for microvascular complications. Our study is the first to show this same legacy effect following bariatric surgery.

Our study included nearly 5,000 racially and ethnically diverse patients aged 20–79 who had type 2 diabetes and bariatric surgery from 2001 to 2011 while enrolled in one of four integrated systems in the Health Care Systems Research Network: Group Health, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Kaiser Permanente Southern California, or HealthPartners (in Minnesota).

Up to seven years after surgery, we found 29 percent less risk of microvascular disease developing in people with diabetes remission than in those whose disease never remitted. And even if their diabetes eventually relapsed, the more time they spent in remission prior to relapse, the less risk they had for developing microvascular disease: For every one more year spent in remission before relapse, the risk for microvascular disease declined by 19 percent.

Waiting too long?

But this effect was lowered by older age, longer duration of diabetes before surgery, being on insulin, and having uncontrolled type 2 diabetes at the time of surgery. I believe that this means that often we are waiting too late to introduce bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes. Younger patients with less severe type 2 diabetes appear to be more likely to experience the maximal benefits from bariatric surgery for remitting diabetes and reducing risk for microvascular disease.

In our study, the risk for developing microvascular disease after surgery was not related to the type of bariatric procedure, race/ethnicity, or preoperative body mass index.

Because of our retrospective observational cohort study design, we cannot say with 100 percent certainty whether surgery caused the lower microvascular disease risk. A randomized controlled trial could do that—and Group Health is currently collaborating in the Alliance of Randomized Trials of Medicine vs. Metabolic Surgery in Type 2 Diabetes (ARMMS-T2D), which is an ongoing prospective study examining the long-term outcomes of four trials comparing bariatric surgery versus intensive medical/lifestyle intervention in patients with diabetes and obesity.

My coauthors are Karen J. Coleman, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Southern California; Rebecca O’Brien, MD, DCh, David Fisher, MD, and Stephen Sidney, MD, MPH, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California; Emily B. Schroeder, MD, of Kaiser Permanente Colorado; Patrick J. O’Connor, MD, MPH, MA, and Nancy E. Sherwood, PhD, of HealthPartners; Sebastien Haneuse, PhD, of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; Andy Bogart, MS, of the RAND Corporation; and Eric Johnson, MS, Mary Kay Theis, MS, MA, and Jane Anau, of GHRI.

National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases awards #5R01DK092317-04 and #1K23DK099237-01 funded our research.