Could ‘deprescribing’ anticholinergic drugs prevent dementia?

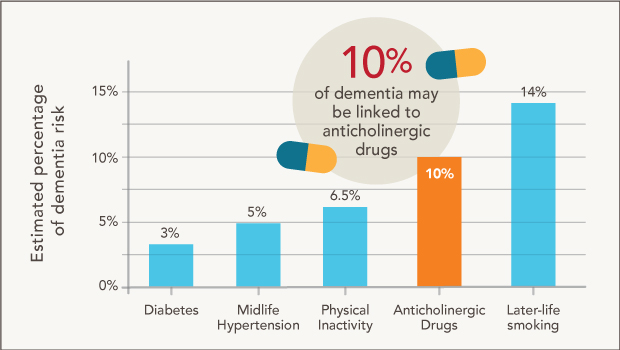

These estimates attributing different percentages of dementia diagnoses to anticholinergic use and various lifestyle factors come from Carol A.C. Coupland, PhD, et al. of the University of Nottingham in “Anticholinergic Drug Exposure and the Risk of Dementia: A Nested Case-Control Study” in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dr. Larson reflects on splashes, ripples—and new research by U.K. scientists, which builds on his earlier findings from the ACT study

By Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH executive director and senior investigator, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI) and vice president for research and health care innovation, Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington

I feel proud and happy whenever Kaiser Permanente Washington research makes a splash. One time that happened was in 2015, when the KPWHRI-University of Washington (UW) Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study published these important results: People had a higher risk for developing dementia after they took commonly used medications with strong anticholinergic side effects at larger doses and for a longer time.

This made a splash because no one had considered these frequently used medications to have long-lasting effects. Rather, the concern was that they could cause temporary delirium and blunting of thinking. An earlier study had suggested this might be possible, and ours confirmed the finding—and extended it.

Given that splash, I’m disappointed that our Systematic Multi-domain Alzheimer's Risk Reduction Trial (SMARRT) is finding how common it still is for older people to use these medications regularly—especially antihistamines and sleep aids like diphenhydramine (Benadryl). I think the reason is that people wrongly assume that these drugs are completely safe because they’re sold over the counter, not by prescription—and they seldom even tell their doctors that they’re taking them.

Newest findings

We need sustained ripples to keep taking our research further and help make needed improvements to personal and public health. That’s one of the reasons why I was delighted to see a large new study in JAMA Internal Medicine that linked exposure to several types of strong anticholinergic drugs to an increased risk of dementia. Using a large database in the United Kingdom, the study included more than 280,000 primary care patients.

Like us, the U.K. team excluded prescriptions in the final year of follow-up, because of the concern that some of the medications—particularly antidepressants—might be prescribed to treat undiagnosed dementia. Also like us, they found around a 50 percent increase in risk for dementia associated with anticholinergic medication use.

Their study had a different design and larger size, allowing them to drill down on individual drug classes and report that the association was strongest for anticholinergic antidepressants, bladder antimuscarinics, antipsychotics, and antiepileptic drugs.

One surprise to me was that they didn’t find an association with antihistamines. But then I remembered that in the U.K., their “Benadryl” contains none of the antihistamine that Americans use most often (diphenhydramine). Instead, it has been replaced by a newer, less anticholinergic antihistamine. In fact, when our results received international media coverage, and U.K. patients worried about taking antihistamines for sleep, the National Health Service started a public education campaign to indicate that there was no reason for concern there.

Anticholinergic side effects are what cause “dry mouth” and “dry eye,” and they come from blocking the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. People tend to produce less acetylcholine as they age. Anticholinergics include medications from various classes, including some older antidepressants like doxepin (Sinequan), antimuscarinics for bladder control like oxybutynin (Ditropan).

Here’s a list of the anticholinergic medications that we included in our study. Older people tend to have more health issues—and to be prescribed many of these drugs. And one of the key findings of the U.K. study is that the magnitude of dementia risk was greater in the “oldest old,” people over age 80. In general, older, more frail people are more likely to have side effects, particularly when drugs affect neurotransmitters like acetylcholine.

What to do?

If you’re taking one of these medications, you may be wondering what to do. My colleagues Shelly Gray, PharmD (a KPWHRI affiliate investigator at the UW), Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD, and I have addressed that question, including good sleep hygiene. The main take-homes are to talk with your doctor to weigh the pros and cons—and explore alternatives.

Remember that difficulty sleeping is common among older people and seldom causes serious problems. I used to say in my practicing days that I never saw a patient who died or had serious consequences from “insomnia”—but I knew about a lot of patients who fell and broke their hip because of a sleeping pill problem. And now we know that non-prescription over-the-counter medications such as Benadryl (diphenhydramine) have some long-term risks as well.

The U.K. researchers estimate that 10 percent of dementia diagnoses may be due to anticholinergic drugs—more than the estimated 6.5 percent for physical inactivity, 5 percent for midlife hypertension, and 3 percent for diabetes—although less than the estimated 14 percent for later-life smoking.

But we need more research to nail down that the link between anticholinergics and dementia—found in observational studies like ours and the new one—is causal and not a coincidence. We also need to find out possible biologic mechanisms at the cellular level, since some people have these side effects while others may be resistant.

I look forward to more ripples and research to guide our way and build awareness about the hazards of overtreatment and ways to counteract the mass marketing of prescription drugs. These campaigns prey on the appeal that “taking a pill” is the easiest way to address many common symptoms of aging. Current projects underway at KPWHRI and elsewhere involve “deprescribing” anticholinergic medications and benzodiazepines. This relatively new area of research is promising. Results to date indicate that carefully reducing medication use by deprescribing is safe and probably benefits many patients.

Healthy Findings Blog

Higher dementia risk linked to more use of common drugs

Further evidence found of association between anticholinergics and Alzheimer's disease in University of Washington / Group Health study in JAMA Internal Medicine.

What if you’re taking an anticholinergic medication?

Study coauthors Drs. Sascha Dublin, Shelly Gray, and Eric B. Larson explore how to balance the risks and benefits of these common medications.

aging & geriatrics

Do drugs cause falls for adults with dementia?

Researchers find a relationship between prescribed central nervous system-active medications and increased risk of falling among older people with dementia.

KPWHRI in the media

Deaths from falls in seniors are up — are prescriptions to blame?

Everett Herald, Jan 6, 2019