Phentermine for weight loss seems safe, effective longer term

Dr. Arterburn discusses reassuring news from his PCORnet study of the most widely used anti-obesity drug in the United States.

By David Arterburn, MD, MPH, a senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute and an internal medicine physician at Washington Permanente Medical Group

As time goes by, we’re recognizing more and more how chronic and tenacious obesity can be. Comprehensive, intensive interventions to achieve lifelong changes in lifestyle — including diet and exercise — are the cornerstone of treatment, with long-term follow-up. But such programs don’t work for up to one in three patients. And weight regain is common after 6 months, the point when such programs can yield weight loss of 5 percent to 10 percent.

Weight-loss medications are one way to help more people to have larger, and potentially longer lasting, responses to lifestyle interventions, as placebo-controlled trials have shown. But these medications tend not to be used broadly, mainly because of lack of insurance coverage, leading to high out-of-pocket costs for patients, but also because of concerns about side effects.

Phentermine is the most commonly used anti-obesity medication in the United States. Back when it was approved for weight loss in 1959, the chronic nature of obesity wasn’t understood as well. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) limited treatment to 12 weeks or less. By contrast, when the FDA approved a new brand-named combination medication, Phentermine/Topiramate-CR (Qsymia), in 2012, it was for long-term use for a year or more.

Many doctors prescribe phentermine, on its own, to patients for more than 12 weeks. And anecdotal reports from many of my colleagues suggested that it was helpful for many patients long-term. But there’s a lack of research on its longer-term safety and efficacy. Phentermine is available as an inexpensive generic medication, but concerns have been raised about addiction and, because of how it acts, cardiovascular side effects. The medication is a stimulant, so it’s possible that it could raise blood pressure. We clearly needed more research to understand the benefits and risk of longer-term phentermine use.

Filling this knowledge gap

In our new study, “Safety and Effectiveness of Longer-Term Phentermine Use: Clinical Outcomes from an Electronic Health Record Cohort,” published today in Obesity, my colleagues and I found evidence of better weight loss with longer-term use of phentermine — up to 2 years’ follow-up. And we didn’t find any link between longer-term use and risk of cardiovascular disease or death up to 3 years from starting phentermine.

To accomplish this study, we used electronic health records from the Patient Outcomes Research to Advance Learning (PORTAL) cohort, part of the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) initiative funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). This cohort included information from 8 health systems in the United States, including Kaiser Permanente (Southern California, Colorado, Northwest, Washington, Hawaii, and Mid-Atlantic) and Denver Health and HealthPartners (in Minnesota). The study was led by my long-time collaborator, Kristina Lewis, MD, MPH, SM, at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, NC.

We studied nearly 14,000 phentermine users, 8 in 10 of whom were women. Their mean BMI was 38, which is 235 pounds for a 5’6” person. But they included people with a BMI as low as 27, which is 168 pounds for a 5’ 6” person. (Obesity starts at a BMI of 30.) Three in 10 of them were prescribed phentermine for more than 3 months. At 6 months, a year, and 2 years after starting phentermine, weight loss was clinically significantly greater among people who used the medication longer-term (more than a year) or medium-term (more than112 days but less than a year) than in people who used it for only 3 months. The 144 people who used phentermine continuously for more than a year had kept off more than 7 percent of their baseline weight at 2 years.

It’s important to monitor patients for their response to phentermine treatment. About a third of people prescribed phentermine lost less than 3 percent of their weight within the first 3 months of starting the drug. These “non-responders” should not continue phentermine treatment, as they are unlikely to experience clinical benefit from it. By contrast, people who had an early response to the medication — losing at least 3 percent of their weight by 3 months — tended to have greater overall long-term success at weight loss with the aid of the medication.

As far as safety goes, we expected to see an increase in blood pressure, but instead found that systolic blood pressure was reduced at 24 months in long-term users of phentermine relative to short-term users. It’s possible that this decrease in blood pressure was due to sustained weight loss in the longer-term users of phentermine. Forty-one (0.3 percent) of 13,972 phentermine users experienced a major adverse event (36 cardiovascular events; 5 deaths), but none of these was among the long-term users.

Impact on obesity treatment

Our study is limited by being observational, by not being a randomized controlled trial, and by having a relatively small sample of long-term users — and it didn’t address the issue of possible addiction. But because of phentermine’s wide availability and low cost, our findings could have a significant impact on obesity treatment in people at low risk for heart disease.

Similar to what we have seen in studies of the combination medication Qsymia, it appears that some patients can safely maintain long-term weight loss with phentermine alone. Still, until we have a change in FDA policy, off-label longer-term prescribing of phentermine should be done cautiously with full consideration of the legal and medical licensure implications, which can vary from state to state.

More importantly, given the low cost of phentermine relative to other weight-loss drugs, this study should motivate a future randomized trial to establish more definitively phentermine’s long-term efficacy and safety.

News

Filling evidence gaps on obesity treatment

Several new grants will fund research on effectiveness, safety, and equitable use of anti-obesity medications.

Live healthy

Comparing different types of bariatric surgery: What’s right for you?

Based on their studies, KPWHRI researchers explain the risks and benefits.

New findings

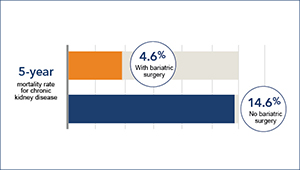

Is bariatric surgery helpful in chronic kidney disease?

David Arterburn and colleagues find that bariatric surgery is linked to lower death risk in persons with obesity and CKD.

News Release

Fewer heart attacks, strokes, and deaths after weight-loss surgery

Oct. 16, 2018—Obese people with diabetes had fewer deaths in 5 years after bariatric surgery vs. usual care, in large, long-term study.