Lung cancer screening guidelines are changing

Now’s the time, Dr. Wernli says, to weigh in on lowering eligible age and pack-years smoked

By Karen Wernli, PhD, associate investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute

For more than 5 years, I’ve been leading research at Kaiser Permanente Washington on screening for lung cancer, which kills more Americans every year than all other cancers that we screen for. My goal is to support people as they consider whether to screen—and to encourage people who have screened in the past to return to screening. By detecting cancer at an early stage, this screening can save lives—but it isn’t as widely used as it could be.

I put patients first in my research, so I established a Patient Advisory Board of Kaiser Permanente Washington members who live on the Olympic Peninsula and get lung cancer screening to understand their needs with screening and to support our clinical efforts. As a patient-centered researcher, I find hearing patients’ experiences is an effective way to incorporate patient needs throughout my research.

Recently, the United States Preventive Services Task Force issued a draft recommendation statement about lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography (LDCT), and now’s the time to comment on it. The Task Force is a group of primary care and internal medicine physicians from across the country who provide national guidance on preventive care. They previously recommended LDCT to screen for lung cancer in 2014. This was a huge milestone for a cancer that had not had any available screening tests.

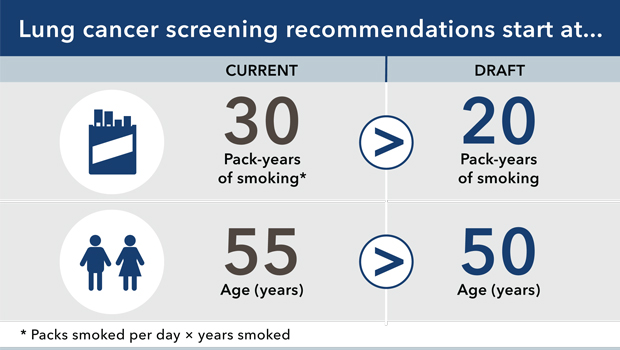

In the current draft recommendation, the Task Force recommends lowering the age of adults eligible to 50 years (from 55 years) and the number of pack-years smoked to 20 pack-years (from 30 pack-years).

Some adults with significant smoking history aged 50-54 years have already received LDCT to screen for lung cancer. However, fewer adults with a history of smoking 20-30 pack-years have been screened. So lowering the number of pack-years smoked from 30 to 20 might be the most important of the changes recommended—and perhaps the most compelling.

What do you think?

The Task Force relies on complex statistical models to understand how policy decisions might affect both the benefits of detecting lung cancer and the harms of lung biopsies that do not find cancer. Their intent is to find the tradeoff that maximizes benefits while minimizing the harms for the largest number of people. They rely on data that asks very detailed questions about an individual’s smoking history, and that’s more thorough than what can reasonably be captured in a brief clinical care encounter.

I have long thought that there is a likely undercount in the capture of smoking history in clinical care: A clinician might ask, “How long have you been smoking? And how much?” By contrast, more complicated questions would ask the number of cigarettes smoked, starting when, and how that changed, accounting for the times when someone quits and restarts. The calculation of pack-years is essentially the number of packs smoked per day times the number of years. So a 30 pack-year history is 1 pack per day for 30 years. By lowering the pack-year history bar to 20 years, clinicians might at least begin to identify more adults who are at increased risk for lung cancer, including people who likely had at least a 30 pack-year history that was underreported in a clinical encounter.

As a draft recommendation statement, the statement is currently up for public comment. The final statement will be published in 2021, with implementation likely soon after and into 2022. Nonetheless, now is the time to begin thinking about how to support the >8.5 million Americans now eligible—and additional Americans who will be eligible—for lung cancer screening.

What do you think? You can comment here until August 3, 2020.

Cancer Research

Research funded to improve cancer screening

Drs. Kamineni and Chubak are among leaders of 2 new large PROSPR awards from NCI for cervical and colorectal cancer screening research.

Read it in News and Events.

cancer research

Group Health’s new lung cancer screening program shows promise

A project to find early cancers is saving lives, thanks to teamwork, writes Jennifer Nazarko, director of medical specialties.