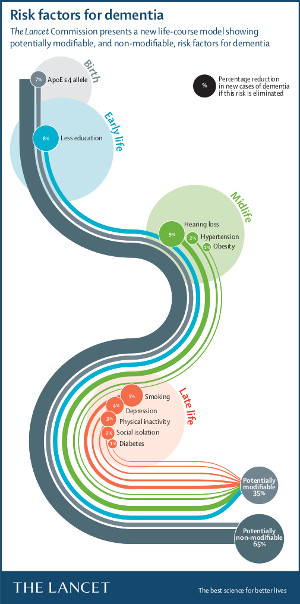

Targeting risk factors could prevent 1 in 3 dementia cases

International experts on The Lancet Commission report, including Dr. Eric B. Larson, identify 9 risk factors from childhood onward

SEATTLE, July 20, 2017—One in three cases of dementia could potentially be prevented if brain health is improved throughout life by targeting nine risk factors, including staying in school until older than age 15 years, reducing hearing loss in mid-life, and reducing smoking in later life.

For the first time, the new report models the impact of risk factors at all stages of life, and quantifies the potential contribution of hearing loss and social isolation as risk factors for dementia.

The Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care is being presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2017, and combines the expertise of 24 international experts to provide a comprehensive review of the disease including 10 key messages to help improve dementia care. One of those experts is Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, executive director and senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI) and vice president for research and health care innovation at Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of Washington. Dr. Larson leads the KPWHRI-University of Washington Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study.

“The Lancet Commission report is very comprehensive and speaks to the need for effective ways to prevent and provide humane, effective care for those affected by Alzheimer’s disease and late-life dementias,” Dr. Larson says. “The finding that in some developed countries age-adjusted rates may be decreasing even as total numbers increase allowed the Commission to recommend widespread adoption of preventive tactics that also lead to improved health in old age.”

He added: “Kaiser Permanente Washington, including the ACT study, is conducting ongoing research in all these areas, and our integrated delivery system health care teams are constantly seeking ways to promote prevention and resilience to late-life declines in brain function while providing personalized care for the many patients and families affected by dementia.”

The latest estimates suggest that the cost of dementia is $818 billion a year and around 47 million people live with dementia globally. The number of people affected is set to almost triple to 131 million by 2050, with the number of cases increasing most in in low- and middle-income countries.

“Acting now will vastly improve life for people with dementia and their families, and in doing so, will transform the future of society,” says lead author Professor Gill Livingston, University College London, U.K. “Although dementia is diagnosed in later life, the brain changes usually begin to develop years before, with risk factors for developing the disease occurring throughout life, not just in old age. We believe that a broader approach to prevention of dementia that reflects these changing risk factors will benefit our aging societies and help to prevent the rising number of dementia cases globally.”

How to prevent dementia?

The report models the impact of nine health and lifestyle factors at various stages in life, including staying in education until over age 15 years, reducing high blood pressure, obesity, and hearing loss in mid-life (45–65 years old), and reducing smoking, depression, physical inactivity, social isolation, and diabetes in later life (over 65 years old). The estimates show the proportion of all dementia cases that could be prevented if the risk factors were fully eliminated.

The study estimates that removing these factors could prevent one in three cases of dementia (35 percent). Comparatively, finding a way to target the major genetic risk factor, the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) ε4 allele, would prevent less than one in 10 (7 percent) of cases.

Of the 35 percent of all dementia cases that could potentially be prevented, the three most common risk factors that could be targeted were:

- increasing education in early life (estimated to reduce the total number of dementia cases by 8 percent if all people continued education until over age 15),

- reducing hearing loss in mid-life (reducing the number of cases by 9 percent if all people were treated), and

- reducing smoking in later life (reducing the number of cases by 5 percent if all people stopped smoking).

Why do these three main risk factors matter?

- Not completing secondary education in early life may raise dementia risk by reducing cognitive reserve, which is resilience to age-related cognitive decline. Education strengthens brain networks and therefore helps continue functioning in later life despite damage.

- Preserving hearing in mid-life may help people to experience a cognitively rich environment and build cognitive reserve, which may be lost if hearing is impaired. But this research is at an earlier stage and could also be a result of social isolation and depression caused by hearing loss, or occur at the same time as brain degeneration that causes dementia.

- In later life, stopping smoking will be important to reduce exposure to neurotoxins and improve cardiovascular health which, in turn, affects brain health.

The Commission recommends

To help reduce dementia risk, the researchers suggest public health interventions including building cognitive reserves by increasing the number of children who complete secondary education, and, in later life, engaging in mentally stimulating activities (such as a combination of engaging in a hobby, going to the movies, restaurants, or sporting events, reading, doing volunteer work, playing games, and having a busy social life). In addition, protecting hearing and treating hearing loss in mid-life may be an important way to prevent dementia, but it is not yet clear if hearing aids counteract the cognitive damage caused by this.

Other interventions likely to benefit are increasing physical activity, reducing smoking rates, and treating high blood pressure and diabetes. The researchers note that such interventions are already available and safe and have other health benefits, but to have the greatest impact they should be incorporated into society.

“Society must engage in ways to reduce dementia risk throughout life, and improve the care and treatment for those with the disease. This includes providing safe and effective social and health-care interventions to integrate people with dementia within their communities. Hopefully this will also ensure that people with dementia, their families, and caregivers, encounter a society that accepts and supports them,” says co-author Professor Lon Schneider, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

While interventions for these risk factors would not delay, prevent, or cure all dementia cases, there is much to gain:

- Other studies suggest that dementia prevalence would be halved if its onset were delayed by five years.

- A 10 percent reduction in the prevalence of the seven health and lifestyle factors could reduce worldwide dementia prevalence by more than a million cases.

The authors note some limitations within their estimates, including that they do not take into account diet and alcohol intake, and some estimates could not be based on global data as such data were not available. They also note that some risk factors may also have an impact during other stages of life, for instance lifelong learning (beyond childhood education) may also be beneficial.

How to achieve equity?

Writing in a linked comment, Professor Martin Prince of King’s College London, UK, says: “Dementia selectively affects the old and frail, women, and the socioeconomically and educationally disadvantaged. It dims the voices of those living with the condition, just when they most need to be heard. The dementia epidemic will be concentrated in low- and middle-income countries where awareness is low, and resources to meet the demand are fewest.”

He adds: “Equity requires that all those affected should be acknowledged as having equal status and value, and accorded equal access to diagnosis, evidence-based treatment, care, and support. We are a long way from achieving equity. The WHO Global Action Plan, with its emphasis on the inalienable human rights of those affected, special attention to low- and middle-income countries, and accountability for achieving universal coverage of health and social care, promises much for the future—if it can be delivered.”

The Commission was partnered by University College London, the Alzheimer’s Society, UK, the Economic and Social Research Council, and Alzheimer’s Research UK. These organizations provided financial and practical help (funded the fares, accommodation, and food for the Commission meetings) and attended author meetings, but had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

In addition to KPWHRI, the Commission was conducted by scientists from University College London, Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust, King’s College London, National Ageing Research Institute, University of Melbourne, University of Exeter, University of Sussex, University of Manchester, Tel Aviv University, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins University, University of Michigan, VA Center for Clinical Management Research, University of Washington, University of Montpellier, University of Edinburgh, Geriatric Medicine Dalhousie University, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Aging and Health, Vestfold Health Trust, University of Oslo, and Innlandet Hospital Trust.

About Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute

Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI) improves the health and health care of Kaiser Permanente members and the public. The institute has conducted nonproprietary public-interest research on preventing, diagnosing, and treating major health problems since 1983. Government and private research grants provide our main funding. Follow KPWHRI research on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn, or subscribe to our free monthly newsletter.

About Kaiser Permanente

Kaiser Permanente is committed to helping shape the future of health care. We are recognized as one of America’s leading health care providers and not-for-profit health plans. Founded in 1945, Kaiser Permanente has a mission to provide high-quality, affordable health care services and to improve the health of our members and the communities we serve. We currently serve more than 12.4 million members in eight states and the District of Columbia. Care for members and patients is focused on their total health and guided by their personal Permanente Medical Group physicians, specialists and team of caregivers. Our expert and caring medical teams are empowered and supported by industry-leading technology advances and tools for health promotion, disease prevention, state-of-the-art care delivery and world-class chronic disease management. Kaiser Permanente is dedicated to care innovations, clinical research, health education and the support of community health. For more information, go to: kp.org/share.

Dementia risk factors

Click here to view full-size image.

Enlightened Aging

Book reading & signing—Enlightened Aging: Building Resilience for Long, Active Life by Eric B. Larson

July 25, 2017

Join Dr. Eric B. Larson in person to hear passages from his new book.

Third Place Books at Lake Forest Park Town Center, 17171 Bothell Way N.E., Lake Forest Park, Wash., 7 p.m.

Aug. 16, 2017

The Elliott Bay Book Company, Seattle Wash., 7 p.m.

Aug. 17, 2017

Queen Anne Book Company, Seattle Wash., 7 p.m.

Averting Dementia

Revenge of the super-agers: Healthy living may avert dementia

After decades of ‘magic bullet’ pursuits, world researchers shine light on the basics: education, good hearing, smoke-free living, and more.

Read about it in LinkedIn.