The Affordability Imperative: Delivering on the Promise

In his Birnbaum Lecture, Dr. Eric B. Larson calls for changes to make health and health care available to all.

Read the transcript below or watch the above video of the entire lecture, which Dr. Larson delivered in the Illsley Ball Nordstrom Recital Hall at Benaroya Hall in Seattle on November 13, 2019.

I’d like to start with a story that some say is an old African proverb. Others think it’s a Buddhist teaching. Let’s just say it’s been validated. It goes like this:

Two young fish are swimming along in their aquarium when an elderly fish swims by. “Enjoy the water!” the wise old fish calls out, and the two just nod and smile. But once the old guy is gone, one youngster looks at the other and asks, “What the hell is water?”

I think we like this story because it shows how easily we become blind to everyday reality and fail to see the most obvious and important truths surrounding us. I tell the story tonight as an invitation for you to step outside the fishbowl of your current awareness of American health care, and to see how lack of affordability is the water we’re swimming in and how it harms us all.

Inside our fishbowl, we’re justifiably proud of American scientific advances—things like effective vaccines, personalized cancer treatment, minimally invasive surgery. But many lack a realistic understanding of American health care’s incredibly high cost and poor performance compared to peer countries.

We spend far more per capita than other wealthy countries do for care—about twice as much Canada, France, and the Netherlands, for example. And yet, Americans have some of the poorest health outcomes among western nations. Our infant mortality rate is higher than every other advanced country and worse than Russia. Maternal death rates are rising at an alarming rate. A recent CDC report showed a deterioration of 46 percent over the past 20 years. U.S. life expectancy is actually in decline. 2020 may mark the first four-year drop since the U.S. Civil War.

Princeton economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton found this decline is due to rising mortality over the past 15 years among people with lower incomes and less education. Death rates are especially increasing in mid-life.

This shift is striking for two reasons: First, it’s so unusual: Death rates almost always go down over time. But now they’re rising among Americans in their 30s through 60s—and especially among those without college degrees. The change is attributed to slower reductions in heart disease—plus rising rates of suicide, drug overdose, alcohol abuse, and cirrhosis. This rise in mortality is directly related to our nation’s worsening income disparities. Case and Deaton have called these the “deaths of despair.”

The second reason it’s so shocking is that this pattern is not happening in any other developed countries.

So, despite all we spend on health care, our nation’s health outcomes are growing worse. It causes me to worry: Have we been living with this for so long that we’re like the fish who doesn’t recognize the water he’s in? Are we so blinded by the glories of “American exceptionalism” and a false sense of security that we can’t see a reality that should haunt every one of us at this surreal juncture of American history?

Spending is at the root of inequity

Waking up to our affordability crisis means recognizing that health care spending is at the root of many problems our country is facing—including, and especially, the widening gap between rich and poor.

Despite passage of the Affordable Care Act, too many people can’t afford the coverage and care they need. And even those with coverage face increasing costs: Some 29 percent of insured adults—or 44 million people—are now considered “under-insured.” This rate has more than doubled since 2003.

When people with no or little health insurance get sick, bills can pile up fast, leaving no money for housing. Many fall into poverty and even homelessness, making it even more difficult to recover financially and physically.

So, if you pass a tent encampment on your way home tonight, you’re right to wonder: How does illness, injury, and lack of treatment and the money to pay for it figure into this scenario? Was affordability the root cause of this person’s dilemma, will it be the consequence, or could it be both?

Regardless, this problem of affordability is the water we’re all swimming in. On a population-wide level, such crises in care and coverage affect everybody. Those with no access to regular, affordable care often avoid treatment until they need expensive rescue care. Providers cover the higher costs, pass them along to insurers, who then raise premiums, making coverage less affordable, especially for those on the lower rungs.

But hear this: The problems of cost in American health care are not unsolvable. We need only open our eyes to the world around us.

Take a look at these figures. This shows how much more the U.S. spends on health care than other wealthy countries do. Obviously, it’s absolutely possible to cover large populations less expensively. We can also see how the U.S. compares with other nations in the number of deaths per 100,000 from treatable medical conditions. The lesson here? Higher spending does not necessarily result in better outcomes. More is not better.

So how did we get here?

How is it that in the richest nation ever, so many seem to accept what’s ethically unacceptable: Decent care and coverage are increasingly out of reach. Have we come to the place where “unaffordable” is simply the water we swim in?

Like many others here tonight, I’ve seen much improvement, thanks to people who were not willing to accept the unacceptable.

I think of Hilde and Bill Birnbaum, Jewish immigrants who fled Nazi-occupied Germany and Poland and eventually helped form Group Health as one of the nation’s first prepaid health cooperatives. With others, they developed a plan based on serving the greatest number by integrating care and coverage and keeping dues affordable for everyday people, especially workers.

I also think of Henry J. Kaiser, who worked with Dr. Sidney Garfield to champion the principle of affordable, prepaid, integrated care with a health plan to serve workers at Kaiser’s California shipyards during World War II.

Today, we might call them “disrupters” because they’re weren’t afraid to challenge the status quo—which was a fee-for-service health care system that left too many bankrupt with medical bills—or suffering and dying without care.

This belief in health care as a right—not a privilege—was also at the core of “The Great Society” initiatives of the 1960s that established Medicare and Medicaid, giving us at that time near-universal coverage. From there, we backslid until the early 1990s when the Clintons, Washington state leaders, and others championed universal coverage again.

Looking back, this was one of the most heartening periods of my career, as I worked with others in leadership of the University of Washington Medical Center. We designed models built around primary care. But when political winds shifted in the mid-1990s, so did the health care sector’s emphasis. Our focus shifted to developing profitable service lines like high-end diagnostics and well-paid elective procedures—all built to compete for margin through fee-for-service medicine. So, I began to ask myself, “Is this really what I want to do with my career?”

In 2002, I heard about a job as head of the Center for Health Studies at Group Health—now Kaiser Permanente Washington. I liked our founder Ed Wagner’s description: “We’re a non-proprietary, public interest research center embedded in an integrated delivery system.”

Group Health had always appealed to me for many reasons, not the least of which was the alignment of financial incentives in such a system. Organizations like Group Health and Kaiser Permanente work like this:

- The organization that provides the care also pays for the care.

- Instead of making money from each service and procedure, we’re incented to keep people out of hospitals and acute care settings.

- We emphasize prevention, deliver sound management of chronic conditions, and shared-decision making based on patients’ and our members’ values.

- We aim to avoid overdiagnosis and overtreatment. Our goal is to practice what some have called “Goldilocks care”: just the right amount—not too little, not too much.

I joined the organization in 2002, amid the constant cacophony of health policy debates. And eventually we celebrated the passage of the Affordable Care Act. Now, that fight continues as various presidential candidates rally for—and revile against “Medicare for All.” And that’s one of the reasons we’re not having a question and answer period after this presentation. (Laughter.)

In fact, it’s very easy in today’s political climate to blame “those damned politicians!”—and the Citizens’ United decision that allows large special interest groups to overspend groups that, like the Birnbaums, want affordable care for all.

Frustrated, we look beyond government, wondering if other stakeholders might provide some relief. But I don’t see much help coming from bottom-line focused hospital corporations, physician groups, specialty associations, pharmaceutical companies, or traditional indemnity insurance plans. All have a strong stake in keeping the status quo.

We hoped that ObamaCare would lead to fundamental change. And indeed, the number of uninsured fell from 44 million to 28 million in the years that followed. But with all the compromises to satisfy powerful and self-interested political forces that in many ways feed off U.S. health care, the Affordable Care Act failed to tackle a central problem: excessive costs and especially prices.

So even if we could achieve universal coverage, we’d be left with this vexing question: How can we improve the health of the whole population if we can’t afford to care for all of it?

That’s not to say we should stop striving for universal coverage, essential work in a just society. But there’s other work needed to make care for all feasible—and that is to focus on affordability.

A fundamentally ethical question

To make this personal, I want to tell you about a symposium we had in this very room about 11 years ago at our 25th anniversary of the Center for Health Studies. I had invited Dr. Mark Smith, the founding president of the California Health Care Foundation, to be our keynote speaker.

Now Mark is not known for pulling punches and he was describing how the average high-option plan at that time had just increased by a whopping 115 percent of minimum wage. He stopped. He looked right at us sitting the front row and said, “You folks at Group Health need to figure out how to do this cheaper.”

You could have heard a pin drop.

“And I don’t mean a little cheaper,” he said. “I mean a lot cheaper.”

He looked straight at us, but he wasn’t going to let the strain on our faces deter him. He went on.

“The fact is, staff-model, integrated health care systems in this country got their foothold because they were 40 percent cheaper than the traditional health care system.”

We all started to stare at our shoes then. And he delivered a line I’ll never forget:

“OK, Smarty Pants,” he asked, “if you’re so integrated, and if your incentives are so aligned, how come you’re not 40 percent less expensive?”

That was 2008.

And although we as an organization have made many significant changes since then, including being acquired by Kaiser Permanente, we have never really answered Mark’s question. That’s not to say we haven’t been competitive—or that we haven’t brought tremendous value to our members. But neither Kaiser Permanente—nor others in our community—have attacked the issue of affordability in the way that Mark was suggesting—nor from the fundamentally ethical way that our founders would have imagined. We haven’t undercut our competitors by 40 percent the way Kaiser and Group Health did in the beginning. Not even close! And we haven’t delivered on the promise of creating health care at a price that people of all income levels can afford.

Why not? Well, to quote my good friend Don Berwick of the Institute for Health Improvement: Reducing waste and cutting costs “is not for the faint of heart.”

First, I think we’re afraid to expose our own privilege. We can say that health care is expensive because of increasing technology, rising drug prices, aging populations, and so on. You all have heard that. But it’s also a fact that many of us in health care make a lot of money. As Don says, that’s not for the faint of heart.

Also, health care now accounts for nearly one fifth of the economy. Heavy health care spending is propping up the prosperity of those privileged to enjoy good fortune. If we were to make drastic cuts to health care costs, what would happen to our businesses, our nation’s job growth, our current economic stability? Fiddling with a key source of a strong economy is definitely not for the faint of heart.

But we must face the fact that every dollar we spend on health care is not available to spend on other needs. Quoting Don Berwick again, “Health care in America is digging ever deeper into our neighbors’ wages, into the vitality of our businesses—and most crucial of all—into our government’s capacity to do other forms of good…. Without changes, millions of people face imminent harm. Our schools totter, our bridges decay, our generosity to the poor wavers, our assistance to the disabled pales, our arts languish, our standard of living hangs in the balance.”

So, to be good citizen stewards, we must ask, how can we shepherd the vast resources we’re given to serve the greatest number?

I would like to propose three interrelated goals to lead the way to affordability—not only for Kaiser Permanente members, but also for others nationally as we lead the way. These goals are:

- To strengthen primary care;

- To address the social determinants of health;

- To focus on value, delivering “all the care, and only the care that will help the patient”—and to measure the value of our work in new ways.

Primary care: More important than ever

Primary care has always been important. But as we struggle with affordability, I think it takes on more significance than ever.

Research consistently shows that higher levels of spending on primary care lead to improved patient outcomes at lower overall costs. A recent study showed that an increase of 10 primary care physicians per 100,000 people resulted in an increase in life expectancy almost three times higher than similar increases in specialty physicians.

International comparisons also align. The U.S. spends just 5 percent to 7 percent of health care dollars in primary care. But in other developed nations, where overall health outcomes are better, they’re spending 14 percent or more.

So, we must find ways to improve access to primary care in our country, especially the ongoing care of those with chronic diseases and older people in general. And we must design primary care to optimize its strengths at addressing prevention, chronic disease management, and behavioral health needs such as care for depression, pain, and overuse of alcohol.

Several pilot projects—including those from our own organization—have shown that intensive primary care—sometimes referred to as a “patient-centered medical home”—can be the antidote: improving outcomes, reducing expensive emergency visits and hospitalizations, and reducing costs overall.

We have learned that moving care upstream—that is, focusing on preventing illness and injury and providing appropriate care to manage chronic illnesses—gets better outcomes.

Still, we have a lot more to learn—especially in the design of care—if we want to do what Mark Smith urged: Make care much less expensive, cut costs by as much as 40 percent. I must admit it’s hard to imagine what could move the dial that far, but it is essential that we work to make sizeable progress. Does it help to design new models of behavioral health services to address behavioral issues that contribute to chronic illness---problems like depression, unhealthy alcohol use, opioid addiction, sedentary lifestyles, and more? Can we realize our hope to improve outcomes by bringing better resources to people with problems we’ve seen as outside the purview of clinical care—issues like homelessness, lack of housing, lack of jobs, education, and economic opportunities?

Addressing social determinants of health is crucial

Which brings me to goal #2: Our crucial need to address social determinants of health. There’s little question, for example, that income correlates with life expectancy. The richest American men live 15 years longer than the poorest men, while the richest American women live 10 years longer than the poorest women.

Some estimate that 80 percent of what creates and destroys health is related to social determinants—education, employment, income, safety, and family and social support. The late and beloved Kaiser Permanente CEO Bernard Tyson said, “Knowing this, we have no choice as health professionals but to look for early opportunities to intervene.”

Within my own research program on healthy aging, we’ve seen how social factors can affect the trajectory of a person’s health. This includes the influence of early childhood experiences such as education and family income on brain development, which affects reserves that determine a person’s cognitive function in old age.

Research shows how a person’s risks for cardiovascular disease, various cancers, mental health problems, and more can be affected by experiences and exposures throughout life, from conception to old age.

One recent study found that “precarity”—that is, precarious social or economic conditions—can cost older people six to nine years of active life expectancy when compared to problems caused by non-communicable diseases.

Let that sink in. It means that older people suffer more loss of good life from social factors such as educational achievement, level of income and wealth, and place of residence than from the problems that we typically target—conditions like hypertension and diabetes.

As one of my heroes, Sir Michael Marmot observes: “Health inequalities and the social determinants of health are not a footnote to the determinants of health. They are the main issue.”

Fortunately, we have a great living laboratory in Kaiser Permanente’s research institutes. Our learning health care system provides care and coverage to more than 700,000 in the Kaiser Permanente Washington region, and 12.5 million nationwide. More than 65 million live in communities that Kaiser Permanente serves.

Projects underway include efforts to better help our patients meet behavior and social needs in the moment. You’ve heard about some of them. Examples include:

- A new role called the community resource specialist, effectively linking primary care patients to community resources.

- A national IT infrastructure initiative, called Thrive Local, which links patients’ social needs to community services.

- And a really bold new effort called the Healthcare Anchor Network, which includes 41 non-profit medical systems. This idea pretty simple: Take the millions of dollars the health care industry spends on new facilities, food, and more—and rather than contract with distant corporations, keep the money local, giving more of our neighbors ample paychecks, stable housing, and nutritious food. So, for example, in construction of our new medical center in South Los Angeles, we specified that 30 percent of all jobs would be for people living within five miles of the site. And among them were 70 previously difficult to employ former prison inmates who were working as plumbers, carpenters, and electricians.

I’m also encouraged by work underway at the Group Health Foundation—the new organization that was established with funds from Kaiser Permanente’s acquisition of Group Health Cooperative. Group Health’s legacy lives on in the Foundation’s strong and explicit focus on equity as it aims to serve disadvantaged communities throughout our state.

As compassionate health care professionals, we can easily imagine new social programs aimed at improving health outcomes. But how do we know that they actually work? That’s where health evaluation capabilities can and must come to the fore. We must use robust analysis to determine the true impact of programs on the health of our communities. Can they make a difference—especially for populations who have seen more than their fair share of health problems? Will they help us reduce health disparities? Can they make health care more affordable?

If so, such leading-edge efforts to address social determinants are entirely consistent with our mission. As Bernard Tyson told us, “Good health is essential to the American ideal of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. As health care professionals, we are obligated to ensure those unalienable rights are not compromised because of demographics, diversity, or socioeconomic status. We should all have an opportunity to thrive.”

Reducing care that provides minimal or no clinical benefit

Which brings me to my third goal: We must focus on reducing low-value care: that is, care that provides minimal or no clinical benefit to patients. It includes tests and procedures that often do more harm than good.

A recent report shows that the U.S. is spending $76 billion to $101 billion annually on overtreatment and care that has low benefit. Add to this all of U.S. health care’s inefficiencies and bureaucratic waste, and some experts estimate we may be squandering as much as $1 trillion per year.

Let me give you an example of low-value care that I heard from a friend who took her elderly mother to a clinic for a blood transfusion. Along with other standard procedures, the staff ordered an electrocardiogram to test for heart problems. When my friend asked why, the nurse said it was “routine.”

My friend told her: “That may be true, but how is this going to help my mother? She’s 95 years old. If you find something wrong, are you going to do heart surgery or not do the transfusion?”

With this, the nurse consulted the doctor and the electrocardiogram was withdrawn, which was a good outcome. But it took this woman’s activist nature to stop the train and avoid a wasteful test that could have led her mother into a whole cascade of unnecessary and potentially harmful care.

It shouldn’t be this way. What we need instead are routines to avoid such waste. The trouble is, in many settings, too many providers have financial incentives to order more tests and treatments, and our climate and metrics really favor “more is better” approaches.

Extra expense comes not only from the tests themselves, but also from incidentalomas. These are the unexpected abnormalities that show up on diagnostic imaging. The scan is ordered to look for one thing, and it finds something completely different. Studies show this happens in 22 percent to 38 percent of all CTs and MRIs. Many patients who get the news of an abnormality may feel blessed. “Oh, boy, I got early detection.” But they may not realize that, left undetected, the issue might never have caused ill health.

Stopping low-value care often involves some degree of disruption—turning against the status quo. It may require telling our coworkers, and perhaps ourselves, that some of our work does not provide value. It may require telling a patient that the test, procedure, or drug they’re asking for is not recommended—because evidence shows it’s not helpful. And it may also require, when caring for patients with late-stage disease—or late-in-life in general, that some forms of care provide no value and may actually diminish their quality of life.

None of this, as Don Berwick has said, is “for the faint of heart.” But he also said, “The magnitude of waste is so high and risks to patients from ineffective care so grave, that it behooves health care leaders worldwide to name the problem of overuse clearly, and to support changes in payment, training, and when needed, regulation to reduce it.”

Remember, our goal is to give “all the care and only the care that will help our patient.”

So, let me tell you about some efforts that give me great hope for positive change. Some are community-wide voluntary efforts.

Initiatives focus on value to patients

First there’s work underway by Washington Health Alliance, a group of 185 organizations statewide who are working to improve health care affordability. Two weeks ago, the Alliance released its first report on low-value care in our state, which found that from 2014 to 2017, our population spent about $703 million on care deemed to be “wasteful” or “likely wasteful.” The good news though, they also showed a significant decrease in such care over that same period. Low-value care fell about 10 percent for the commercially-insured and 24 percent for the Medicaid-insured.

Still, there’s much room for improvement among all providers, especially considering that low-value care affects more than 800,000 individuals each year in our state.

At Kaiser Permanente Washington, we have several initiatives to address this. For example, we’re working hard to fight back harms caused by the opioid epidemic. It would be hard to overstate the damage caused nationwide by this medically induced, overuse disaster and its resulting scourge of addiction. So, I’m pleased that our Institute recently won three very large grants from the National Institutes of Health’s new “HEAL” initiative. One involves a primary care-based intervention delivered by nurses, a second is a cognitive behavioral therapy approach delivered by telehealth, and a third is a trial of acupuncture in older adults.

We’ve also recently developed and shared an innovative program for rural clinics in a five-state region, called “Six Building Blocks for Reducing Opioid Overuse.” Its resources are freely available online and are being used by the state’s Department of Health, the CDC, and others.

Meanwhile, Kaiser Permanente Washington’s Learning Health System Program is working closely with our Puyallup Medical Center on a pilot to develop a comprehensive pain management program, including better access to alternatives like massage, acupuncture, and chiropractic care.

Another area where all providers must seek to deliver the best value is in the cancer screening. Our challenge is to avoid overdiagnosis, which can lead to harm through needless radiation, surgery, or other treatments. But such problems can be minimized by designing care around a patient’s specific risks.

That’s where our research and delivery system have excelled for decades. We were the first system in in the nation to adopt a risk-based breast cancer screening program. Such programs help people make reasoned, personalized choices about screening.

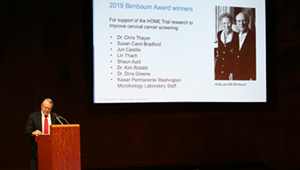

Our researchers now use massive amounts of data from patients who undergo screening and treatment so that we’re always learning and applying that knowledge to improve care. We also employ and explore new cancer screening modalities. The HOME Trial of the HPV test for cervical cancer screening—the work honored tonight with the Birnbaum Award—is a superb example.

One more area that holds great potential for positive change is late-in-life care. We often talk about “end-of-life care” that’s provided through hospice services when a person is near death. But I’m talking about the time when people may be frail and have complex medical problems such as advanced dementia, but they do not have a terminal diagnosis. Too much care can be invasive, unnecessary, not curative, and can often be harmful.

On one hand, it only makes sense for our society to devote more resources for care of the sick and elderly. It’s the right thing to do. That’s where there’s need, and we have a lot to offer. On the other hand, we need to protect vulnerable, elderly people from getting too much care and care that is not valuable and is often harmful.

We must also recognize that hospitals are typically not a good place for frail elderly people. Our own research in the ACT study showed that hospitalization for acute illness is linked to greater cognitive decline for older adults.

Patients with dementia have significantly higher rates of hospitalization for all causes. We have shown that up to two-thirds of those hospitalizations are for conditions that can often be treated by primary care providers and the patient stays at home.

Understanding this, a team at Kaiser Permanente Washington recently conducted a small successful pilot project for persons with late-stage dementia. We provided home visits, along with phone-based support that helped keep people out of emergency departments and hospitals.

This work continues in programs to bring care like this to other groups as well, such as those with renal failure, high-risk cancer, and other advanced conditions. Our preliminary work on care costs in the last three years of life suggests that we might forego up to $30 million to $40 million dollars annually if we could care for people in their homes or places of residence versus an emergency departments or hospital settings.

It’s related to a whole body of work at Kaiser Permanente that we refer to as “Dignified Journeys.” This includes using predictive modeling to identify members who might benefit from having advanced-care-planning conversations with their physicians and caregivers, and then planning their care to ensure that it aligns with their preferences and values. In so doing, we may avoid unwanted, unnecessary care. And if we can do this on a population-wide basis, we’ll ultimately make care better and more affordable for all.

We need better measures of care improvement and affordability

It’s fulfilling to do this work—identifying low-value, or even harmful, care and testing ways to address it. I’m very encouraged by national initiatives led by groups such as the Lown Institute and JAMA’s current series titled “Less is More,” which have helped shine light on important research.

But the effort is challenging. Much work is needed to learn new and better ways to measure the value of our care. As the saying goes, “You can’t improve what you can’t measure.” And it seems to me that the American health care system spends too much energy measuring growth in revenues, and not enough measuring improvements in health and affordability.

When it comes to quality, most organizations focus on regulatory metrics. While many metrics address important areas like safety and prevention, some measures lead to unintentionally rewarding overdiagnosis and overuse.

Here’s an example of how it can go wrong: According to a recent report in JAMA Internal Medicine, 9 percent of all women dying of late-stage cancer are still getting routine mammograms. I imagine many of these women got their screening in organizations striving to meet screening metrics on a population-wide basis. But at what cost to the patient who got no benefit from spending her precious time in the mammography suite?

So, what can we do differently? How about developing systematic ways to better measure care that actually produces value, and care that does not. We need to find new, creative ways to do this.

We need better tools. American health care seems to be stuck in a bygone era, using tools like Epic, the ubiquitous electronic medical record system that was really designed to optimize revenues in fee-for service systems. And it does a great job of tracking how many tests and procedures clinicians order and billings go up and so do bills. But it wasn’t designed to make clinicians more effective. And it’s clearly not helping to make care more affordable.

And we need better payment models. The Affordable Care Act launched several experiments in value-based financing, all with mixed, or essentially nil, results. While experts disagree about the best path forward, many are focusing once again on the secret sauce that made integrated, pre-paid models like Kaiser Permanente famous: managing the care of populations via capitation. That is, paying an organization per patient enrolled in their care, giving health care teams incentives to provide care that’s valuable to patients’ health and well-being.

Challenges exist, of course. One is that we health care providers see ourselves as only having good intentions—so we believe the tests we order, the care we recommend must be valuable. And yet we have our doubts. In some recent surveys, practicing physicians estimate that 20 percent to 30 percent of the care they provide doesn’t add value. We’ve actually probably known it all along.

So, we simply have to change.

The goals I’m proposing—to strengthen primary care as foundation to better health for all; to address social determinants of health; to focus on providing value and to measure the value of our care in new ways—are just some among many directions to take.

But as individuals striving to achieve affordable health care for all, we can do this: We can commit to working together to find solutions and to provide the leadership to make real lasting changes.

As Jonas Salk, who developed the polio vaccine, has said, “There is no such thing as failure. There is just giving up too soon.”

And to those of us who work for Kaiser Permanente, I have a particular message: Let’s hold on to our organization’s inherent and remarkable qualities as a not-for-profit, integrated, learning health care system. And let’s continue to be the kind of community that leaders like Bernard Tyson inspire us to be: passionate, moral, hard-working people who actually give a damn about the inequities and suffering we see around us.

In closing I’d like to share this quote by an environmental activist, Wendell Barry:

“We have lived by the assumption that what was good for us would be good for the world…. We have been wrong. We must change our lives, so that it will be possible to live by the contrary assumption that what is good for the world will be good for us. And that requires that we make the effort to know the world and to learn what is good for it.”

Thanks for joining me in this effort.

Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, is a senior investigator and former executive director at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute. His also former vice president for research and health care innovation at Kaiser Permanente Washington.

2019 Birnbaum Highlights

Watch excerpts of the 2019 Birnbaum Lecture

Check out these five clips from Dr. Eric Larson's Birnbaum Lecture, “The Affordability Imperative: Delivering on the Promise of Health and Health Care for All,” on Nov. 13, 2019: