- Our Research

- Research Areas

- Addictions

- Aging & Geriatrics

- Behavior Change

- Biostatistics

- Cancer

- Cardiovascular Health

- Child & Adolescent Health

- Chronic Illness Management

- Health Informatics

- Health Services & Economics

- Healthy Communities

- Medication Use & Patient Safety

- Mental Health

- Obesity

- Preventive Medicine

- Social Determinants of Health

- Vaccines & Infectious Diseases | COVID-19

- Our Scientists

- Collaborate with Us

- Our Publications

- Research Funding Sources

- Research Areas

- News and Events

- Get Involved

- About Us

- Live Healthy

Mapping and Organizing Your Codesign

The ENSPIRE Playbook

Setting the Stage | Mapping and Organizing Your Codesign | Conducting Your Codesign | Producing and Sharing Your Codesign Projects | Evaluating Your Codesign | Recommendations Based on Lessons Learned | About the ENSPIRE Study

Shape your codesign approach

Shape your codesign approach

![]()

- What organizational needs or deadlines affect planning?

- How many codesign teams will you have?

- How often will teams meet?

- What is the expected outcome of codesign?

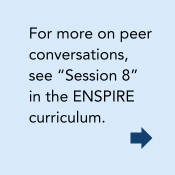

ENSPIRE created a 10-week codesign strategy

Codesign can vary from a process completed over several hours or several days, to a series of meetings over many months or even a year.1,2,3,4

For ENSPIRE, we invited 27 long-term care staff from 10 centers to develop tailored COVID-19 vaccination-promotion materials over several weeks. Codesigners worked in 5 teams, each with a shared racial/ethnic identity. They were also trained in nonconfrontational vaccine conversations to help promote the materials to their peers.4,5

The codesign process — including training, design workshops, and reviews — lasted 10 weeks.

ENSPIRE built on the following codesign approaches, adapting their methods to fit our needs, the communities we were partnering with, and our study goals:

Boot Camp Translation (BCT)6 is a successful community-based participatory research method for codesigning materials, communicating information, and promoting behavior change for health issues including hypertension, diabetes, colorectal cancer screening, chronic pain, and cardiovascular disease. BCT’s efficacy is likely due to an approach that involves:

Boot Camp Translation (BCT)6 is a successful community-based participatory research method for codesigning materials, communicating information, and promoting behavior change for health issues including hypertension, diabetes, colorectal cancer screening, chronic pain, and cardiovascular disease. BCT’s efficacy is likely due to an approach that involves:

- Forming partnerships between researchers and local community members

- Increasing relevance of evidence-based interventions by using language and concepts that resonate locally

- Disseminating messages via effective community and personal channels

LINCC (Learning to Integrate Neighborhoods and Clinical Care)7,8 was a project that used codesign to develop and implement a new primary care role: a lay staff person to connect patients with community resources. Patients were equal partners with clinic staff in designing this new primary care service. LINCC used a 4-day design event and subsequent 1-day “check and adjust” event a year later.

References

1 Kelly A. Schmidtke et al, “A Workshop to Co-design Messages that May Increase Uptake of Vaccines: A Case Study,” Vaccine, September 2022, p. 5407.

2 “Co-Designing with Kids with Complex Needs,” Inclusive Design Research Centre, co-design.inclusivedesign.ca/case-studies/co-designing-with-kids-with-complex-needs/, accessed September 27, 2024.

3 Nathaly Aya Pastrana et al, “Improving COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake: A Message Co-Design Process for a National mHealth Intervention in Colombia,” Global Health Action, August 29, 2023.

4 Sarah E. Brewer et al, “Engaging Communities in Preventing Human Papillomavirus-Related Cancers: Two Boot Camp Translations, Colorado, 2017–2018,” Preventing Chronic Disease, January 2, 2020.

5 “Talking about Vaccines: HEART Method,” Immunity Community, immunitycommunitywa.org/talking-about-vaccines/, accessed September 27, 2024.

6 Ned Norman et al. “Boot Camp Translation: A Method for Building a Community of Solution,” Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, May-June 2013.

7 “Partnering with Patients as Equals in Co-Designing Primary Care: Examples and Tools from the LINCC Project,” Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, 2017, kpwashingtonresearch.org/application/files/5615/5866/2635/LINCC_ParteringWithPatientsCareDesign_Final.pdf, accessed September 10, 2024.

8 “Community-Led Co-design Kit,” Inclusive Design Research Centre, co-design.inclusivedesign.ca/, accessed September 10, 2024.

Select the populations where you will recruit codesigners — use your problem/challenge/question to drive this

Select the populations where you will recruit codesigners — use your problem/challenge/question to drive this

![]()

- Who is impacted by the problem or issue you are addressing?

- What kinds of experience should your codesigners already have, and what can they learn along the way?

- Who will want to engage with the issue and team up with others like themselves? Are there others who are important to include but may need more effort on your part to recruit and engage?

- Which of the following attributes would be appropriate for your codesigners — or what other attributes are relevant to your problem/challenge/question and the impacted community?

- Place where people live, work, play

- Age

- Language(s) spoken

- Impact of a particular health issue/condition/disease

- Connection to an institution like a school, health system, or workplace

- Ethnicity or racial identity

- Gender identity

- Lived experience

![]()

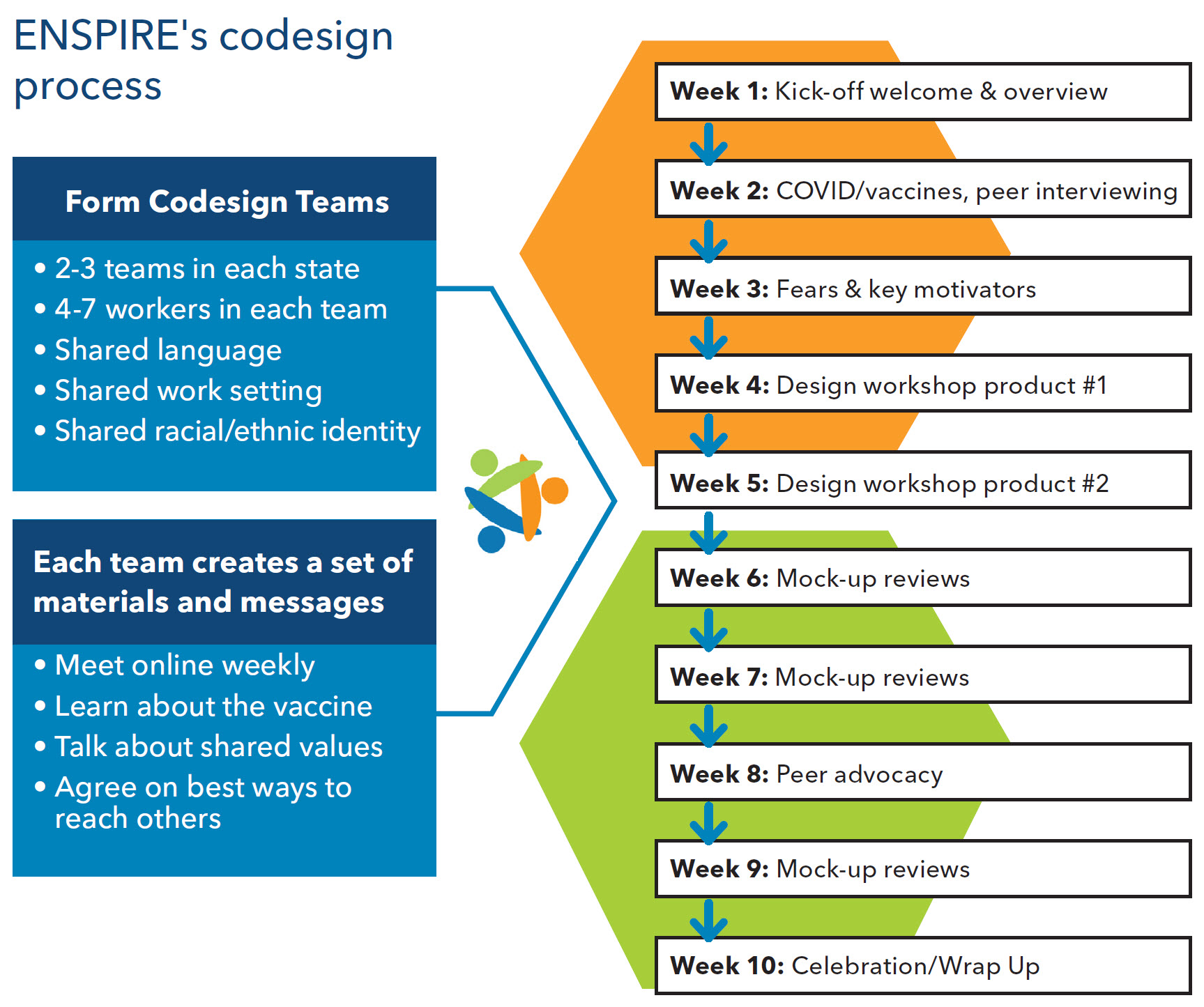

ENSPIRE codesigners shared work setting, racial/ethnic identity, location

In our ENSPIRE project, we decided to frame our codesign teams around attributes we thought most important in designing promotional materials for COVID-19 boosters:

- Place: Live in Georgia or Washington state (where we were conducting the research)

- Connection to workplace: Work at any job in the long-term care centers we were partnering with

- Racial/ethnic identity: Matching largest groups working in long-term care in Georgia and Washington

- Language(s): Any language that fits with selected racial/ethnic identities

- Impact: All long-term care staff had been impacted by COVID-19 during the pandemic

- Age: Any age

- Gender identity: All genders

We focused on race/ethnicity because:

- Research and other reports indicated that race and culture influence attitudes toward vaccines

- Some racial/ethnic groups were disproportionately affected by COVID-19

- This approach allowed for the creation of a safe, comfortable environment

We used survey data and conversations with administrators to identify the racial/ethnic identities most represented among our partnering long-term care centers. We identified:

| WASHINGTON | GEORGIA |

|---|---|

| Black/African American, African, Latino, Asian Pacific Islander, and white | Black/African American, Afro Caribbean, and white |

This would be our starting point for recruitment:

Build a codesign project team and define each person’s role

Build a codesign project team and define each person’s role

![]()

- How will you organize your project team?

- What will be the key elements of your codesign team(s)?

- Who will be responsible for activities and behind-the-scenes tasks?

- Who will lead the project team?

- Who will provide support to leaders, co-facilitators, codesigners?

![]()

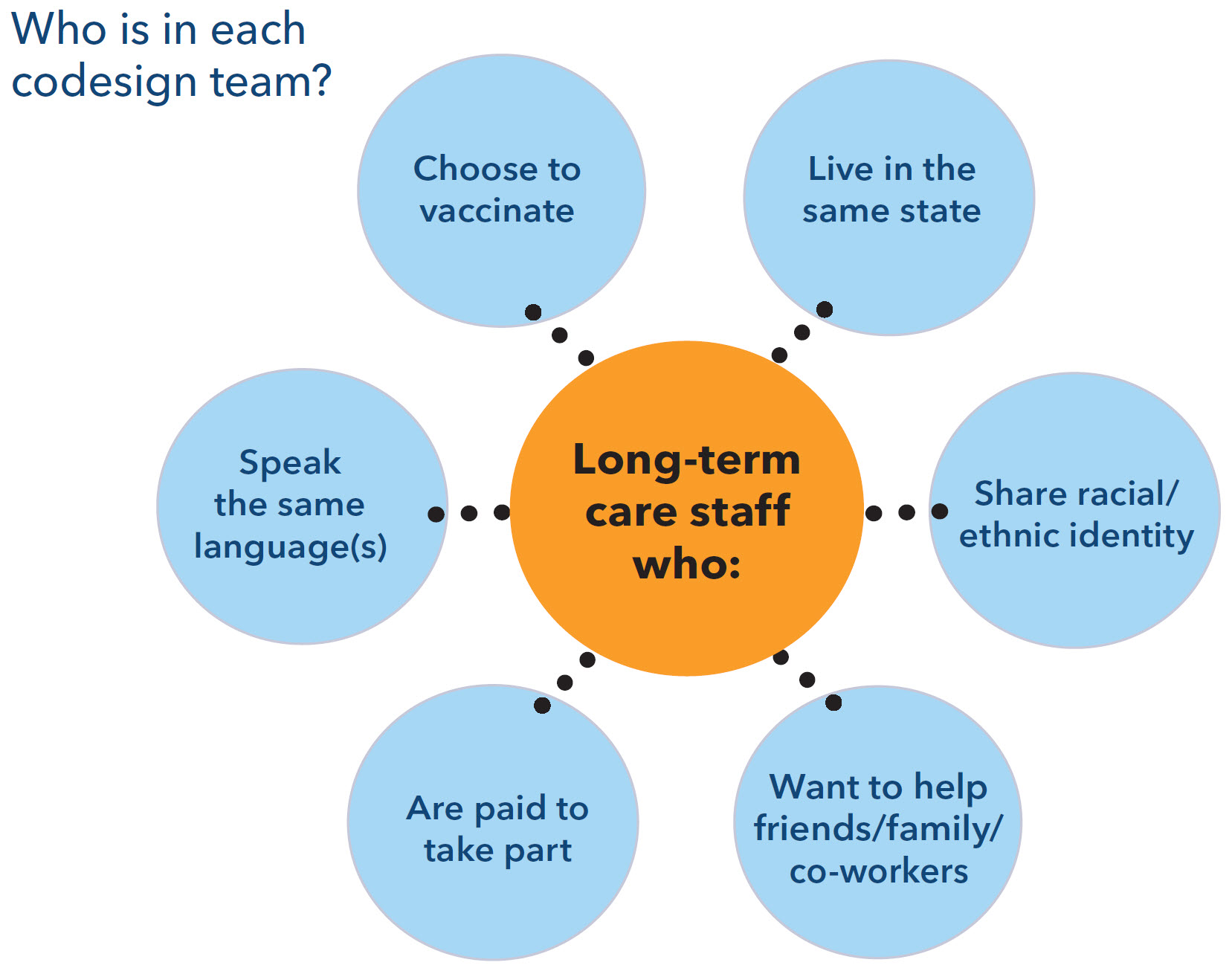

ENSPIRE’s project team included admin support, leadership, co-facilitators (staff and community), codesigners, and a communications production team.

ENSPIRE’s staff had deep experience collaborating with community partners, facilitating group work, understanding the public health topic, and training peers and partners. Some staff had experience doing codesign.

Administrative support

We were fortunate to have administrative support to provide a lot of behind-the-scenes technical and logistic support. These team members arranged incentive payments, conducted screening interviews, provided technical support, and generally kept the project going when an extra set of hands was needed.

Codesign leadership

We asked one staff person to be primarily responsible for leading the codesign portion of our study. This person worked with another colleague to develop early drafts of the curriculum, keep timelines and schedules, serve as a communications point person, and lead regular meetings with the facilitators of our codesign teams. This person was also primarily responsible for maintaining and distributing final versions of the curriculum to all facilitators.

Co-facilitators

Each codesign team had two facilitators:

- One from the research team

- One with extensive community-based experience.* Many of the community-based co-facilitators had direct experience working in long-term care, which was very helpful.

All co-facilitator pairs shared racial/ethnic identity with their codesign team members. This was important, as we wanted codesigners to feel comfortable and confident talking openly with their fellow codesigners and their co-facilitators. We also valued the cultural expertise the co-facilitators would bring to codesign.

*The team in Washington that was Black/African American/African Immigrant was led by 3 co-facilitators: an African Immigrant researcher, an African American community-based co-facilitator, and an African Immigrant community-based co-facilitator.

Codesigners

Codesigners were all employed as staff in a long-term care center and living in Georgia or Washington state at the time of codesign. They were asked to attend weekly codesign meetings, complete several “homework” assignments, and take part in follow-up evaluation interviews after codesign. All codesigners on any given team shared racial/ethnic identity with each other and with their co-facilitators.

Communications production team

The communications production team included a team lead, a copy editor, a graphic designer, and a video editor. One communications staff member was assigned to each codesign team to attend select meetings and gather input and feedback from codesigners. The communications production staff worked as a team behind the scenes, as all 10 products created through codesign needed production support (writing, editing, design).

Decide who will best facilitate your codesign sessions

Decide who will best facilitate your codesign sessions

![]()

Facilitator number, content expertise, attributes

- How many facilitators will you have for your codesign team(s)?

- What are the attributes your facilitators need to have?

- What is more important for your project: having facilitators who match with codesigners on attributes (for example, profession, race/ethnicity) or who have content expertise related to the codesign topic?

- Which skills/knowledge/experiences will your facilitators need in advance versus which can be trained?

- What are some interpersonal skills your facilitators will need (for example, making participants comfortable, encouraging vibrant conversation)?

Meeting scheduling and logistics

- How long will your codesign process take, and how does that impact who you bring on as facilitators?

- Who will determine the codesign meeting times/days — and how does this impact who is available to facilitate?

- Where will your facilitators be based — will activities be in person or online?

Locating facilitators

- Will your facilitators be existing staff members of your project?

- How will you locate, identify, and recruit additional facilitators if needed?

Compensating facilitators

- Will facilitators be paid staff, contractors, volunteers?

- What is the best way to compensate facilitators? How does this fit your organization's administrative system?

![]()

Facilitator number, content expertise, attributes

ENSPIRE decided to have co-facilitator pairs for each codesign team because we recognized that the process would benefit from:

- Community-based co-facilitators with life experiences similar to our codesigners’ and, if possible, expertise in long-term care

- Staff-based co-facilitators with ongoing experience with the study

Co-facilitator pairs would also allow for support and coverage if a facilitator became ill.

Our community-based co-facilitators needed a unique skillset, and finding people who fit each team was challenging. Here are some of the characteristics we were looking for in co-facilitators:

- Very flexible availability to attend possible meetings afternoons, evenings, weekends

- Availability to work with us over the next 6 months

- Group facilitation skills, including confidence and skills to facilitate meetings online

- Shared racial/ethnic identity with codesigners

- Reliable access to technology during all sessions

- Effective communications skills

- Willingness to talk about promoting the COVID-19 booster and develop promotional materials

- Good time-management skills

- Experience in long-term care, if possible

Meeting scheduling and logistics

Our 10-week codesign timeline was determined by:

- The content we needed to convey to codesigners

- The goal of each team producing 2 motivational products

- The desire to include a buffer week to accommodate unforeseen barriers or slowdowns along the way

Our co-facilitators needed to be available for 12 weeks total:

- 2 weeks of orientation/training

- 10 weeks of codesign meetings

We prioritized accommodating our codesigners' work schedules when we set meeting times and dates. Our co-facilitators had to be available at those same times. Even if they had full-time employment, they would continue to be available throughout our codesign period.

Locating facilitators

We cast our nets far and wide to identify and recruit good candidates for our community co-facilitators. This included reaching out to:

- Community co-investigators and research team connections

- Community partner organizations

- Our national advisory committee

Once we had interested candidates, our staff facilitators interviewed their prospective co-facilitators.

Compensating facilitators

See Conducting your codesign for information about payment and support.

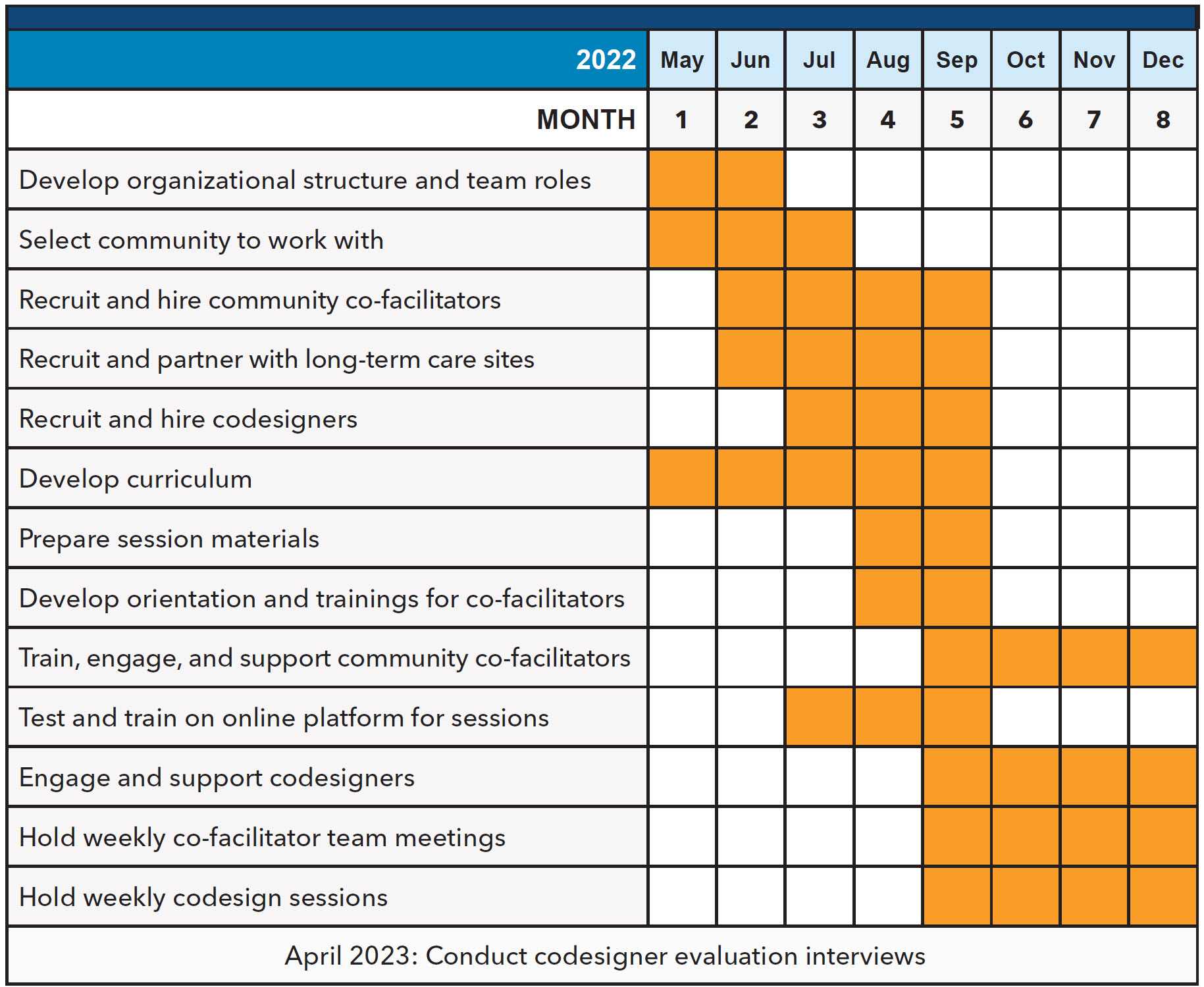

Build a timeline — from planning through codesign

Build a timeline — from planning through codesign

![]()

Staff resources

- How many staff members do you have available to plan and support codesign? How will this affect your planning and codesign timeline?

Facilitation needs

- How many facilitators do you need to hire and train?

- How much training will they need?

Institutional/organizational considerations

- How long does your hiring or contracting process usually take?

Finding and supporting codesigners and their schedules

- Do you have community partners who can help you invite codesigners, or will your staff need to conduct outreach?

- Do you have codesigners who can make time for this (for example, retirees or people who will do this as part of their regular job) or will they engage in this work in addition to a regular job?

- Do codesigners have professional experience related to your codesign topic — both content and process — or is this a new experience for them?

Curriculum needs

- How much structure do the facilitators need in a curriculum to run the codesign process?

Product development as part of the codesign process

- Will you need to include time for your staff or a marketing team to design materials based on what the codesigners decide to include?

- Who do you need to coordinate with about production of the final products?

- How quickly do you need the final products?

![]()

ENSPIRE had an 8-month timeline for codesign, from start to finish

ENSPIRE was a large research project conducted with a robust staff.

- We were fortunate to have administrative staff as well as leadership to support the project.

- We also had staff codesign facilitators who already had a lot of facilitation experience and only needed training specific to the curriculum.

- We relied on our own staff to do in-person outreach to invite codesigners from our partner long-term care centers.

Key timeframes:

- Planning: 4 months

- Codesign: 10 weeks

Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute for:

Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute

Phone: 206-287-2900Fax: 206-287-2871

Contact us

Sign up for our newsletter

Policy on Conflict of Interest

Nondiscrimination Notice and Language Access Services

Land Acknowledgment

Our Seattle offices sit on the occupied land of the Duwamish and by the shared waters of the Coast Salish people, who have been here thousands of years and remain. Learn about practicing land acknowledgment.