Bariatric surgery keeps weight off in long term

Weight loss persisted for 10 years with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in Dr. Arterburn’s large multisite study of veterans

by David Arterburn, MD, MPH, senior investigator at Group Health Research Institute and affiliate professor in the University of Washington School of Medicine

Obesity is a chronic and challenging disease, as the patients and clinicians who struggle with it know all too well. Claims of quick fixes abound, but success over the long haul is often elusive. That’s why I’m so excited about the latest findings from our research on bariatric surgery.

Lasting weight loss

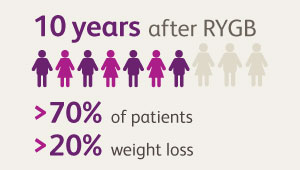

In a large study of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients around the country, we found that those who had Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery lost much more weight than did matched patients who had no bariatric surgery. And the vast majority of patients sustained most of this weight loss in the long term—up to a decade. We published our findings, “Bariatric Surgery and Long-Term Durability of Weight Loss,” in JAMA Surgery today.

In an accompanying commentary, "Myths Surrounding Bariatric Surgery," Jon C. Gould, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin calls the results "remarkable" given the high follow-up rate and hopes they will help counter the perception that all metabolic and bariatric surgery patients gain their weight back.

At 10 years after RYGB surgery, we studied what had happened with 1,787 veterans. Because veterans are loyal users of the VA health care system, we had a remarkably high (82 percent) follow-up rate. We found that more than 70 percent of the veterans who had RYGB surgery had maintained a weight loss of at least 20 percent of their baseline weight at 10 years. And 40 percent of the patients who had RYGB surgery had more than 30 percent weight loss at that same point. The RYGB patients had maintained significantly greater weight loss (21 percent more) than had matched patients with no surgery.

The weight loss after RYGB was remarkably durable: At 1 year, patients treated with RYGB had lost 31 percent of their baseline weight; and at 10 years, these patients had maintained an average 29 percent weight loss. Only 3 percent of patients who had RYGB had regained their weight back to within 5 percent of their baseline weight.

Patients with severe obesity seldom achieve significant weight loss without treatment, but the nonsurgical patients in our study had modest (7 percent) weight loss after a decade, likely due to age-related changes, although it is possible that some of these patients may have taken advantage of the VA’s behavioral weight management program.

Caution about sleeve gastrectomy

Sleeve gastrectomy is now the most commonly performed bariatric surgery in the United States: 52 percent of all bariatric procedures in 2014, and rising. Because it’s a relatively new procedure, we couldn’t evaluate sleeve gastrectomy for the full decade that we studied RYGB. But at four years after surgery, we had sufficiently high follow-up rates to compare the three currently most commonly used types of bariatric surgery: sleeve gastrectomy, RYGB, and adjustable gastric banding:

- We found that weight loss was greatest for the RYGB patients (28 percent of their baseline weight), and only 3 percent of them regained all their lost weight (within 5 percent of baseline).

- By contrast, the 379 patients who had sleeve gastrectomy had significantly less weight loss (18 percent). And 15 percent of them regained all their lost weight.

- The 246 patients who had adjustable gastric banding lost the least weight (11 percent)—and nearly one in three of them regained all their lost weight by four years after surgery.

Before ours, only three large multisite U.S. studies had compared weight change across different bariatric procedures with more than two years of follow-up. Accumulating long-term evidence about the safety and durability of sleeve gastrectomy is particularly important, given its recent introduction.

Our results suggest sleeve gastrectomy’s effects on weight loss may be significantly less than those of RYGB surgery in the long term.

Big picture

Before our work, bariatric surgery had already been shown to result in significant weight loss for patients with severe obesity. And even though it is common for at least some of that weight to be regained, certain types of surgery have been linked to declines in risks for diabetes, cancer, and heart disease.

|

|

|

But evidence had been limited about how long post-surgery weight loss would last, compared to nonsurgical matches and across bariatric procedures. Also, most prior research was done among women in their 40s, whereas our population was mostly men, with a mean age of 52 at surgery. So our study fills several important evidence gaps.

Of course, obesity is a complex problem that demands multiple approaches by individuals, clinicians, and society at large, including changing food policies to encourage healthy eating and changing our built environments to encourage regular physical activity. And surgery is not for everyone.

But for many people with severe obesity, bariatric surgery—specifically RYGB—is looking more promising as a long-term means of improving health, thanks to our new results. These findings will further inform shared decision making about treatment options for obesity to help surgical candidates choose what is best for them. This is crucial because earlier research has shown that people tend to have unrealistic expectations of weight loss from bariatric surgery.

The first author of our paper is my long-time colleague, Matthew Maciejewski, PhD, of Duke University and Durham VA Medical Center in Durham, NC. Our colleagues are at Duke University, Durham VA Medical Center, VA North Texas Health Care System, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Northwestern University, and JAMA.

Our work was funded by the Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs (IIR 10-159). Dr. Maciejewski was also supported by a Research Career Scientist award from the Department of Veterans Affairs (RCS 10-391).