‘Fighting back’ against COVID-19: Remembering a historic trial

Dr. Lisa Jackson, right, a KPWHRI senior investigator, confers with pharmacist Michael Witte, left, on March 16 in Seattle before the first injections of the experimental COVID-19 vaccine were given. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Lisa Jackson, MD, MPH, Kaiser Permanente Washington senior investigator, recounts the genesis of a groundbreaking vaccine

Republished from the March/April 2021 issue of WSMA Reports with permission of the Washington State Medical Association.

Over the course of the last year, Lisa Jackson, MD, MPH, has found herself in the spotlight. As senior investigator at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI) in Seattle, Dr. Jackson and her research team led the phase 1 clinical trial for the COVID-19 vaccine developed by the National Institutes of Health and Moderna — one of the vaccines now being administered across the country that promises to help end the pandemic.

This January, WSMA Reports asked Dr. Jackson to share some thoughts on the momentous scientific achievement of producing an effective vaccine in less than a year, and why working on the trials has become the highlight of her distinguished career.

WSMA Reports: When news of the novel coronavirus started emerging from China, what was going through your mind? When did it become apparent to you that it could be a major threat?

Lisa Jackson: I was reminiscing at the start of the year about where my work stood in January 2020. KPWHRI had a small, but well-established, immunization study team, and it was winding down a couple of studies. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) had recently awarded us another round of Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit (VTEU) funding: That meant our work was covered for the next 7 years, but we didn’t know what we would be doing; we thought probably some influenza vaccine trials and maybe even a malaria vaccine trial.

That all changed on Jan. 21. I was at the NIH that day for the kickoff meeting for the new funding cycle for the Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Network, which includes KPWHRI and 9 other centers. We were all listening to a talk by Dr. [Anthony] Fauci regarding this new virus that had recently been identified in Wuhan, China. During that talk, all our phones started going off with the news that the first U.S. case of COVID-19 had been identified in a community near Seattle.

I think most everyone in the room knew then that we were facing a crisis. That was the beginning of the rest of 2020. Shortly after I flew back to Seattle, we received a notice that a vaccine was being developed for this new virus by the NIH and this company called Moderna, which no one had ever heard of. It asked for any VTEU sites interested in conducting the phase 1 clinical trial of this vaccine to apply. I consulted with my colleagues, Maya Dunstan and Barbara Carste, and we agreed to go for it. The next week, we were awarded that study. That was the end of life as we knew it.

WSMA Reports: Your team led the phase 1 trial for the NIH-Moderna COVID-19 vaccine that began on March 16, a little less than 2 months after the first confirmed U.S. case was identified in Washington. What made it possible to start the trial so quickly?

Lisa Jackson: Once we were chosen to launch the phase 1 trial, everyone on the team dropped everything else in their lives, including other work, family relationships, and whatever else they normally spent time doing. We were working nonstop on preparing for this trial; that single-minded focus provided great time efficiencies. We quickly ramped up our team by adding investigators, nurses, and pharmacists. By the time we gave the first injection on March 16, the number on our team had more than doubled to 22 people from 9.

The support we received from others was tremendous. When we needed approval for something from the Institutional Review Board or the NIH or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, we were put at the front of the line. A step that might have taken months in a typical trial would be completed in a week because testing the vaccine was the highest priority. In just a matter of days, several thousand people completed online questionnaires to be considered for 1 of 45 spots in the trial.

None of this would have mattered if the NIH and Moderna had not been able to produce the vaccine so much faster than is typical with more traditional vaccines. Once Chinese scientists shared the genetic code for the virus in January, scientists at Moderna were able to engineer a piece of mRNA that was designed to provide a blueprint for cells to use to make the coronavirus spike protein, prompting an immune response to that protein. To have a potential vaccine for a new disease and start to evaluate that vaccine in a clinical trial within 2 months was remarkable.

The phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials for the vaccine ended up overlapping with the phase 1. Usually, these stages progress sequentially. While all the participants in the phase 1 trial at KPWHRI had received their 2 doses of vaccine, the phase 1 trial still had another year or so to go when we began work on the phase 3 effort. KPWHRI was 1 of nearly 100 sites involved in the phase 3 clinical trial, which had some 30,000 participants. By moving ahead more quickly on each phase, Moderna was able to report in November its interim results that were the basis for the FDA granting its emergency use authorization.

WSMA Reports: Was there anything that surprised you in the process of conducting the trials?

Lisa Jackson: We never dared to hope for 94% effectiveness. The fact that the vaccine developed by Pfizer and the NIH-Moderna vaccine had almost identical, incredibly high positive results is not something I ever would have predicted. Up until these vaccines, the FDA had never even approved an mRNA vaccine for use. That’s how new this technology is.

I've probably done 60 or 70 clinical trials in my 25 years as director of a vaccine research program. The timeline for this vaccine is way beyond what we've ever seen. Just to develop the protocol can take a year or longer. So, to have the whole program for this vaccine go from development to performing the phase 1 trial, to performing the phase 3, to getting amazing efficacy results, and now actually have it be administered to people in less than a year is truly unprecedented. And that’s an understatement.

Unfortunately, this success is also attributable to the huge surge we’ve seen in COVID-19 cases in the United States. The phase 3 trial was designed to perform the first analysis for efficacy when 53 volunteers had developed the disease. Because of the surge, we reached that number of cases much sooner than we had expected, and the first analysis included 95 cases, with the final analysis including 269 cases.

WSMA Reports: With the vaccine rollout now underway, what do you think the biggest obstacles might be in vaccinating a large portion of the U.S. population?

Lisa Jackson: By the time your readers see this in March 2021, I think that we will have been through a long, dark winter. The vaccines are not going to be able to have an impact on the overall pandemic, in my opinion, at this stage, because not enough people will be vaccinated. There's an individual benefit, but it's not absolute.

There’s a saying about vaccines that is repeated often: They don't work if you don't use them. While the trials showed that the vaccines are highly effective, they are not 100% effective: A small set of volunteers who received the vaccine in the trials did develop COVID-19 infections. We need to avoid pockets in which there are unvaccinated people, as we've seen with outbreaks of measles, for example, that have occurred in clusters of unvaccinated people at a certain school or in a certain geographic location. Having a vaccine available doesn't help if you're creating situations where there can still be highly efficient transmission, because there are many susceptible people. It’s going to take a lot of work to get to high levels of coverage.

WSMA Reports: Do you think the speed with which COVID-19 vaccines were developed and the mRNA technology used will have any implications for future vaccines?

Lisa Jackson: I hope so. Because of major breakthroughs in our ability to manipulate mRNA, we may now be able to design vaccines much more quickly as new disease-causing viruses arise. Vaccine makers may no longer need to place fragments of the attenuated virus into vaccines or create the proteins needed to fuel an immune response. Instead, they can make vaccines with the mRNA that prompt our cells to create the specific proteins needed to mount an attack against the invading virus. It seems to be much easier to manufacture large batches of mRNA vaccines than the previous types, potentially eliminating years of waiting for production to scale up.

WSMA Reports: How can physicians and scientists reassure the public about the safety of the vaccine and about the importance of getting vaccinated?

Lisa Jackson: The different COVID-19 vaccines have gone through extensive clinical trials. While the process was faster this time around, no steps were skipped. These studies produced extensive evidence that these vaccines work and are safe. At roughly 95%, their efficacy rate is much higher than the minimum 50% needed to gain approval. The FDA vetted this information carefully before granting its emergency use authorizations.

The public should rest assured that the public health system will be closely monitoring the vaccines in the coming months to identify immediately any problems and to find ways to enhance their use. I anticipate devoting more of my time to these surveillance efforts in my roles as KPWHRI’s principal investigator of the Vaccine Safety Datalink Project, a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kaiser Permanente, and other health systems to monitor the safety of vaccines once they have been approved for use.

WSMA Reports: What will your team be working on next?

Lisa Jackson: We are continuing to follow the volunteers we enrolled in the phase 1 and phase 3 trials of the NIH-Moderna vaccine. We are also engaged in 2 other trials of COVID-19 vaccines developed by Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson, and by HDT Bio Corp., a biotechnology company in Seattle. While our trials to date have been for adults 18 and over, we need to learn how best to use the different COVID-19 vaccines in teenagers and children. Our plan is to either launch new trials for participants under 18 or to amend the existing trial protocols to allow for younger participants.

There remains much work to be done in the vaccine studies. Working on these trials — having the opportunity to participate in these amazing efforts that are so important for us and for the world — has been and will probably continue to be the highlight of my career. It allowed us to start fighting back and to begin tamping down this raging epidemic.

BY KATIE HOWARD, Washington State Medical Association

1-year anniversary

Looking back: Our COVID-19 vaccine trial at 1 year

Dr. Rita Mangione-Smith reflects on the year since KPWHRI launched the world's first clinical trial for a COVID-19 vaccine.

1st vaccine shot

COVID-19 vaccine trial volunteer on the shot heard 'round the world

On March 16, 2020, Jennifer Haller became the first person to be injected with a COVID-19 vaccine in a clinical trial.

Research

COVID-19 pandemic research at KPWHRI

Having long tracked infectious diseases and tested vaccines, KPWHRI now focuses on the novel coronavirus.

News

NIH-Moderna COVID-19 vaccine receives FDA Emergency Use Authorization

The investigational vaccine that KPWHRI’s team first tested shows an efficacy rate of about 94% as research continues.

News

COVID-19 vaccine well tolerated, generates immune response

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored phase 1 trial tested mRNA vaccine.

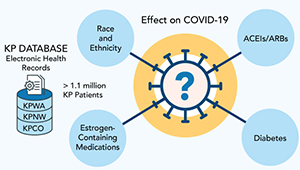

Drugs, diabetes, disparities

Studying COVID-19 risk and outcomes

Dr. Sascha Dublin tells how studies of KP electronic health record data can improve COVID-19 treatment and prevention.

News

Youth under 18 eligible for COVID vaccine trial registry

A registry started by KPWHRI last year has sped up studies needed to protect the world against the novel coronavirus.