Computer-aided detection does not improve breast cancer screening

CAD raises screening costs without benefit to patients and may miss cancers, large national BCSC study shows

SEATTLE—Newer, costlier, and higher tech don’t necessarily mean improved—and computer-aided detection (CAD) of breast cancer screening seems a case in point. So found a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) study in JAMA Internal Medicine: “Diagnostic Accuracy of Digital Screening Mammography with and without Computer-aided Detection”

The study used information from more than 625,000 digital mammograms read by 271 radiologists at 66 facilities across the United States. In the whole study, as in various subgroups of women, CAD improved no measure of accuracy of screening mammography: how often cancers were detected, how often they were missed, or how often something was incorrectly labeled as cancer. Radiologists detected cancer in about 4 of every 1,000 women—and invasive cancer in about 3 of those 4—whether interpreting the nearly half-million digital mammograms with CAD or the nearly 130,000 without it. CAD did find more noninvasive, stage-0, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), but finding more DCIS has not been determined to improve outcomes for women in screening programs.

“Even more troubling, when we studied the 107 radiologists who interpreted both with and without CAD, we found that a given radiologist tended to miss more cancers when using CAD than when he or she didn’t use the software,” lead author Constance D. Lehman, MD, PhD, said. “It may be that radiologists reading with CAD are overly dependent on the technology and ignore suspicious lesions if they are not marked by CAD.” Dr. Lehman is the director of breast imaging and co-director of the Avon Comprehensive Breast Evaluation Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. She is also an affiliate researcher at Group Health Research Institute (GHRI) and the University of Washington.

Wasting health care resources?

“We’re concerned that using CAD for screening mammography does not benefit women—and may even increase the chances a radiologist misses a breast cancer,” the paper’s senior author Diana L. Miglioretti, PhD, said. “We question the policy of continuing to charge—and pay—for this technology.” Dr. Miglioretti is the dean’s professor of biostatistics in public health sciences at the UC Davis School of Medicine and a senior investigator at GHRI. An accompanying editorial concludes that Medicare should no longer cover the cost of CAD.

CAD mammography is estimated to cost $400 million a year in current U.S. health care spending, with no added value and in some cases worse performance. This is likely a gross underestimate, Dr. Miglioretti said, as it is based on Medicare reimbursement of $7 per exam for CAD, which is only a third of what many private insurers pay for this technology.

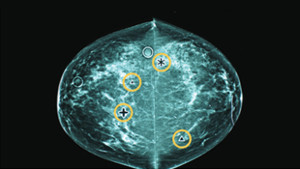

CAD is a type of digital mammography in which a computer program marks areas on a mammogram that may be abnormal. Then a radiologist needs to determine whether they might actually be abnormal: Around three CAD marks per screening test are “false positives” that are normal, creating extra work for radiologists, who must also seek abnormalities that CAD missed—because, like any test, it’s not perfect.

How mammography with CAD spread

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved CAD for mammography in 1998, but it wasn’t widely used until 2002, when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) approved reimbursement for CAD for mammography. Studies since then have been equivocal about whether screening with CAD helps detect breast cancer in community practice.

“Despite lack of evidence of benefit, use of CAD mammography has taken off,” said Drs. Lehman and Miglioretti’s coauthor Diana S.M. Buist, PhD, a senior investigator at GHRI. By 2012, their study found, 83 percent of all screening mammograms were digital and interpreted with CAD. “During this same time period, evidence has accumulated demonstrating no added benefit and potentially more harm from this technology,” Dr. Buist said. “Yet insurance companies, employers, and women are still paying for CAD.” You can read a blog post by Dr. Buist about this study. An earlier BCSC study found that, compared to older film-screen methods, digital mammography raised costs with only small health benefits, but that technology is nearly universal now.

Drs. Lehman, Miglioretti, and Buist’s coauthors are Robert D. Wellman, MS, a GHRI biostatistician; Karla Kerlikowske, MD, a professor of medicine, epidemiology, and biostatistics at UC San Francisco; and Anna N. A. Tosteson, ScD, the James J. Carroll professor at the Norris Cotton Cancer Center and professor in the Department of Medicine at the Geisel School of Medicine and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice at Dartmouth in Lebanon, NH.

The National Cancer Institute (P01CA154292) supported this study. The NCI-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) (HHSN261201100031C, P01CA154292) and PROSPR U54CA163303 further supported data collection. Several state public health departments and cancer registries throughout the United States in part supported collection of cancer and vital status data used in this study.

Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium

The Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) is the nation's largest and most comprehensive collection of breast cancer screening information. It's a research resource for studies designed to assess the delivery and quality of breast cancer screening and related patient outcomes in the United States. The BCSC is a National Cancer Institute-funded collaborative network of seven mammography registries with linkages to tumor and/or pathology registries. The network is supported by a central Statistical Coordinating Center. Currently, the Consortium's database contains information on over 14.3 million mammographic examinations, 3.0 million women, and 154,000 breast cancer cases (127,000 invasive cancers and 27,000 ductal carcinoma in situ).

Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $760 million and major research centers in AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine. In July 2015, MGH returned into the number one spot on the 2015-16 U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

About Kaiser Permanente

Kaiser Permanente is committed to helping shape the future of health care. We are recognized as one of America’s leading health care providers and not-for-profit health plans. Founded in 1945, Kaiser Permanente has a mission to provide high-quality, affordable health care services and to improve the health of our members and the communities we serve. We currently serve more than 12.4 million members in eight states and the District of Columbia. Care for members and patients is focused on their total health and guided by their personal Permanente Medical Group physicians, specialists and team of caregivers. Our expert and caring medical teams are empowered and supported by industry-leading technology advances and tools for health promotion, disease prevention, state-of-the-art care delivery and world-class chronic disease management. Kaiser Permanente is dedicated to care innovations, clinical research, health education and the support of community health. For more information, go to: kp.org/share.

Media contacts

Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center

Katie Marquedant

617-726-0337

Media contact

For more on Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute news, please contact:

Bianca DiJulio

bianca.s.dijulio@kp.org

206-660-8333

After-hours media line: 206-448-4056

healthy findings blog

For mammography, radiologists do better without computer help

Based on a new BCSC study, Dr. Diana Buist tells of technology that adds cost to breast cancer screening—without improving outcomes. Dr. Marc Mora comments.