Breast-biopsy delays after mammogram more likely for Black, Asian women

Study suggests disparities at screening sites may influence lag in follow-ups

Black and Asian women are more likely than white women to experience significant delays in getting breast biopsies after a mammogram identifies an abnormality. Moreover, those delays appear to be influenced by factors specific to screening sites, which may stem from structural racism, according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

“Even after adjusting for multiple factors thought to contribute to delayed diagnosis, we still see persistent disparities among minority women, particularly Black women. To me, this suggests that other underlying factors are contributing to these differences in time to biopsy,” said Marissa Lawson, MD, the study’s lead author. She is an acting instructor of radiology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

In the study, Black women were at the highest risk of not having a biopsy within 90 days of having an abnormal screening mammogram.

“We need more studies that evaluate and intervene on specific structural racism and health care barriers to receiving recommended diagnostic testing,” said study co-author Erin Bowles, MPH, manager of the collaborative science division at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute. “Barriers could include lack of biopsy services at screening facilities, limited appointment availability on evenings or weekends, transportation access, or insurance coverage. We also need to talk with Black women and understand how we can help address these barriers from their perspective, and then work to remove those barriers.”

The study reviewed data on 45,186 women whose screening mammograms had shown a tissue abnormality that called for a biopsy to ascertain whether it was cancerous. Across the study population, 34.6% of women were not biopsied within 30 days, 16% were not biopsied at 60 days, and 12% were not biopsied within 90 days.

The delays are concerning because previous studies have indicated that the benefit of screening diminishes with delays in diagnostic testing, and these delays may be associated with later-stage disease at diagnosis.

Using the time-to-biopsy of white women as the benchmark, the researchers found that:

- At 30 days out, Asian women had a 66% higher risk of not undergoing a biopsy, Black women, 52% higher, and Hispanic women, 50% higher.

- At 90 days out, Black women had a 28% higher risk of not undergoing a biopsy. Among Asian women and Hispanic women, the risk was 21% higher and 12% higher, respectively.

With that unadjusted model, the researchers then examined whether specific factors of individual patients, their neighborhoods, and their screening facilities influenced the time to biopsy among women of different races and ethnicities.

“Controlling for individual- and neighborhood-level factors, we saw that risk was not very different from the unadjusted model,” Lawson explained. “But when we controlled for the screening facility attended, delays in time to biopsy were reduced.”

Digging deeper, the investigators examined the influence of predesignated site-level factors — academic affiliation, screening-exam modality, and the availability of onsite biopsy — and were surprised to find that none of those factors explained the overt difference.

“The findings indicate that there are some differences among the screening facilities associated with the time to biopsy. We just don't know what the specific differences are,” Lawson said.

The authors wrote, “Structural racism, within and beyond health care, may contribute to these differences.”

The screening sites are all associated with the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, a U.S. network of breast imaging registries that is representative of the country’s population in terms of age, race, and ethnicity.

“Our findings highlight an opportunity for radiology departments to consider where they can commit resources to improve wait times for biopsy. This could include implementing changes in that diagnostic pathway such as using navigators to help guide patients through the process of scheduling exams and procedures,” said Christoph Lee, MD, MS, MBA, senior author on the paper. Lee is a professor of radiology at UW and an affiliate investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (P01CA154292, R01CA266377, R35CA197289, U01CA199218, R50CA211115, T32CA009168, U54CA163303), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCS-1504-30370), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01 HS018366-01A1), the Lake Champlain Cancer Research Organization (021800), the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, the University of Vermont, the University of California, Davis, and the Placer County Breast Cancer Foundation.

This has been adapted from a news story on this study by UW Medicine, University of Washington.

News

Race, income, education affect access to 3D mammography

The technology’s potential benefits to detect breast cancer earlier are not equally shared among all women, researchers find.

Healthy findings blog

Prioritizing breast screening during COVID-19

As cancer screening rates rebound, Erin Bowles, MPH, reflects on maintaining “pink ribbon” awareness year-round.

Research

Roundup of 3 recent studies on breast cancer screening

New research spotlights overdiagnosis, MRI before surgery, and a new way of predicting breast cancer risk

Cancer screening

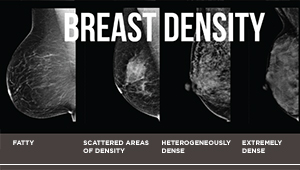

Breast density is a risk factor for older women, too

Findings in JAMA Network Open could help guide decision-making about breast cancer screening for women 75 and older.