Dementia risk screening tool shows promise in health care setting

In a new study, a tool to help discover undiagnosed dementia performed well in 2 separate health systems

More older adults with undiagnosed dementia can potentially be identified through a screening tool called eRADAR, a new study finds. ERADAR — short for EHR (electronic health record) Risk of Alzheimer’s and Dementia Assessment Rule — is a tool developed using data from a prior research study of dementia, to help clinicians decide which patients might benefit from additional screening. Results were published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine. The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging within the National Institutes of Health.

“Around 50% of people living with dementia are undiagnosed,” said lead author Yates Coley, PhD, assistant biostatistics investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI). “Because of this problem of underdiagnosis, there are people living with the effects of dementia who could benefit from a diagnosis, which might increase their ability to access support and resources. We wanted to test the eRADAR tool, which was developed in a limited research setting, to see if it could be useful in a more general clinical setting and, ultimately, make it easier to provide patients with a diagnosis and support those living with dementia.”

The study team tested the accuracy of eRADAR in primary care clinics at Kaiser Permanente Washington and the University of California San Francisco Health (UCSF), using retrospective electronic health records for more than 130,000 patients. The tool was first developed using data from the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) Study at KPWHRI, a long-running aging study with participants who take part in regular assessments. The ACT Study is also funded by the National Institute on Aging.

The eRADAR tool does not diagnose dementia, but it can identify patients who may be high risk and could benefit from follow-up screening. The eRADAR prediction algorithm calculates a patient’s score based on routinely collected clinical data such as a person’s age, other health conditions (such as diabetes), vital signs such as weight, and medications. Because there is not a set definition of what constitutes a high-risk score, the researchers examined what proportion of eventual dementia diagnoses would be caught — and which would be missed — at different thresholds of risk.

Testing eRADAR in a real-world setting and in 2 very different health systems allowed the researchers to find out whether the model performed well in different patient populations. In a given year, patients at Kaiser Permanente Washington and UCSF with an eRADAR score above the 90th percentile were more than 4 times more likely to receive a new dementia diagnosis, respectively, compared with the average patient. The AUC (area under the curve), a summary measure of sensitivity and specificity, was 0.84 at Kaiser Permanente Washington and 0.79 at UCSF. Values above 0.7 are generally considered strong for this measurement. An AUC of 0.5 is no better than flipping a coin, while an AUC of one represents perfect prediction.

The model’s success in both health systems is a strong indication that it could be used in a general patient population, the researchers explained. As an integrated health system, Kaiser Permanente Washington patients receive most of their care within the system. UCSF patients sometimes receive care outside the system, and diagnostic and coding methods can also be different across health systems. These kinds of differences can make it difficult for a tool developed in one setting to work well in other settings. To address this, the researchers adapted some of the variables used in the original risk score so that it could be calculated in another health care system (UCSF). This adaptation could make the risk score generalizable to other non-integrated health care systems.

“To see that the model did well at UCSF was really encouraging,” said Coley. “We want to do work that is immediately relevant to our patients here, but we also want to know that we can help patients outside of Kaiser Permanente.”

Deborah Barnes, PhD, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at UCSF and study co-author, agreed. “UCSF serves a more diverse patient population with a broader range of insurance types. We were really pleased to see that eRADAR performed well in our system which, like most U.S. health care systems, does not use an integrated care model.”

Models that rely on patient records from health care visits can show variability over time if there are shifts in health care practices or data collection. However, eRADAR performed consistently over a study period of more than 10 years at Kaiser Permanente Washington and 6 years at UCSF.

The researchers also looked at the model’s performance for different racial and ethnic groups, in order to ensure that using it in a clinical setting would not contribute to inequities in health care. The analysis showed that the overall performance of the model was excellent and similar across different racial and ethnic groups, and further trials will continue to look for any inconsistencies.

This first phase of model validation in 2 health care systems looked only at patient records and whether patients were subsequently diagnosed with dementia in routine clinical care. The next step is a pragmatic trial in both health systems to evaluate the impact of offering additional screening for patients with higher risk scores. This next phase of the study will help the researchers evaluate the benefits of incorporating eRADAR into regular clinical practice and will give them more data about the rate at which dementia is underdiagnosed in different populations.

The study authors pointed out that any follow-up to eRADAR screening in clinical practice should not be overly invasive or expensive, since not all patients classified as high risk by eRADAR will have dementia, and that care should be taken in communicating with patients about their scores and any follow-up screening to avoid undue anxiety or concern over a possible diagnosis. To better understand the risks and benefits of targeted dementia screening from the patient and family point of view, the study plans to gather extensive data from patient participants and their families about their experience with the intervention, and the impact on their lives of getting a dementia diagnosis.

“The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force currently doesn’t make any recommendation for or against universal dementia screening,” said Coley. “We need to think about both the risks and benefits of universal screening, because it can cause stigma or distress for patients, and there are limited treatments to reverse memory problems. However, getting a dementia diagnosis might let some people get additional help and support, including getting checked for other medical problems. It also lets them and their families plan for the future. Our hope is that the tool we developed could shift that risk-benefit balance by identifying a population that would most benefit from a diagnosis and subsequent increased care and support.”

By Amelia Apfel

Co-researchers

Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD

Senior Investigator

Abisola Idu, MS, MPH

Collaborative Biostatistician

,

Learn About the ACT Study

Understanding brain aging

For over 30 years, the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) Study has been advancing our understanding of cognition, aging, and better ways to delay and prevent Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

ACT Study

Roundup of 3 recent studies on dementia risk

Researchers explore links between hearing loss, military service, and cognitive decline — and look at timeliness of diagnosis.

From research to practice

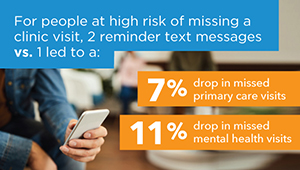

Predicting and preventing missed clinic visits

Biostatistician Yates Coley reports on new predictive analytics work that’s decreasing missed visits at KP Washington.