Patients may not be telling their doctors what matters to them most

KPWHRI’s VITAL study discovers six domains that people with chronic illness too rarely discuss with their care providers.

Imagine a man named Albert, a professional baker in his early fifties who’s avidly interested in genealogy and his family’s history. Most nights after work, he goes for a walk with his dogs, then eats a healthy dinner, limiting desserts because he knows he should. Spending time with his family is important to him. What he really looks forward to are the nights his family gathers in the living room to work on projects. Albert just loves settling into his favorite chair to read history books or to log onto his computer for genealogy research.

Albert also has diabetes, heart disease, depression, and arthritis in his knees and hands. He regularly visits his health care clinic where his provider team collects information such as his blood sugar levels, weight, medication regime, and amount of exercise.

Health care’s standard approach to caring for patients like Albert is to create a plan that ensures safe and effective treatment. Chronic conditions like Albert has require ongoing care. When a patient has several of these, the recommended treatments may conflict, which makes care planning especially complex.

Diabetes can cause eyesight problems, which means Albert may be at risk of losing his ability to read. Arthritic changes in his hands could impact his ability to use a computer. If his physician knew how much (and why) he valued each of these abilities and activities, they could spend time in the clinic creating and revising a care plan that supports what’s important to him.

Most health systems fail to link patient values to care

Unfortunately, health care often misses opportunities to link what’s personally meaningful to patients and what’s clinically recommended because most systems aren’t set up to consistently and routinely connect these two worlds. But a Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute research team led by James D. Ralston, MD, MPH, is looking for ways to make it happen.

“Patients motivated me to do this project,” says Dr. Ralston, a practicing Kaiser Permanente internist. “In my patients living with multiple chronic health conditions, I saw those conditions changing their ability to do things that were important to them and impacting nearly every aspect of their lives. I often thought we could be taking better care of them.”

One key is closing a communication gap between patients and providers that’s well documented, but that hasn’t yet been bridged. Shared decision-making tools exist, but they usually focus on specific treatment decisions, such as, “Should I get a knee replacement?” There’s a current lack of research evidence to support the necessity of capturing what’s most important to patients for planning their care. There’s also limited evidence on effective ways to elicit and clarify patient values, or the types of values of different patient populations.

Exploring ways to close this gap, Dr. Ralston and his colleagues launched the Valuing Important Things in Active Lives (VITAL) study and recently published a key finding: Patients often don’t share what’s really important to them with their health care providers.The findings resulted from a deep dive into how patients think and what matters to them. It was an important first step that’s shaped the direction of Dr. Ralston’s team’s work.

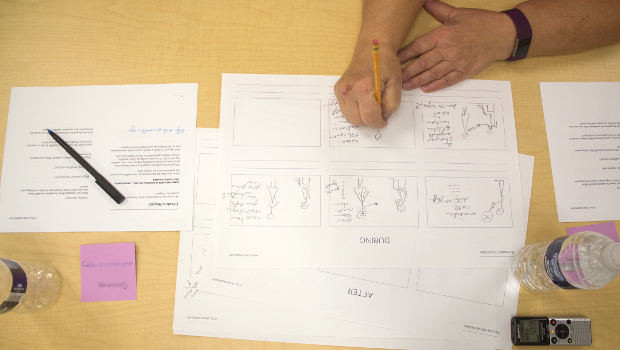

People with chronic illness created storyboards about their experiences during a study-sponsored workshop.

Physicians often talk about diseases and management of conditions, while patients talk about symptoms, Dr. Ralston explains. Patients might not talk about their values in health care appointments because they don’t think certain information is important. It’s almost as if doctors and patients speak two different languages.

Drawing on the expertise of designers and artists

The VITAL team’s methodology is purposely non-traditional. “We decided early on that if we were going to ask patients such personal questions, and to open up to us, that we should do this in their homes, says Dr. Ralston. “It felt important that we ask for this information in the place that was likely to be the most comfortable for them. I would be surprised if we could’ve gotten this information in any other setting.”

Ms. Catherine Lim, a KPWHRI research associate who has a master’s degree in interaction design, and Andrew Berry, a PhD student in human-centered design and engineering, led the home interviews, using a method known as photo elicitation. This involved asking patients prior to the home visits to take pictures representing what matters to them. Then, using traditional research methods, the team sifted through the interview data to identify six domains of “what matters” to patients for their well being and health:

- Principles

Beliefs and standards to live by, such as “having a purpose.” (Example: Albert’s sense of connection to his ancestors.) - Relationships

Social connections with family, friends, coworkers, neighbors, or community groups. - Emotions

Feelings, moods, or states of being, such as the sense of satisfaction Albert feels when he finds a new link to his family’s roots. - Activities

Important pursuits, such as Albert’s genealogy research, or a hobby like gardening. - Abilities

Including physical or mental capacities or skills, like Albert’s vision or being able to fully use his hands. - Possessions

Including objects and significant spaces, such as Albert’s computer, and the family room in his home.

The discovery of the six domains was important—and only the beginning of this work. Many research studies get similarly far as Dr. Ralston’s has, but stall on the next step: Understanding how, and in what ways, to translate their findings into health care.

With the domains defined, VITAL began reaching out to an ever-wider circle of patients and providers. The team conducted phone interviews with patients, asking them about the six domains and if anything was missing. They also held a series of design workshops where patients, physicians, medical assistants, and nurses envisioned a future where patients and providers routinely communicate about patient values and plan care accordingly. Participants were encouraged to share ideas from their own experiences.

Imagine a day when a patient like Albert can go to his primary care clinic for a check-in, and talk about what’s most important to him for his well-being and health. Everyone on his care team would have what they need to more easily make the connection between Albert’s love for reading and care of his diabetes, or what it takes to keep his hands functional for his job as a baker and his genealogy work at home. They would all work together on an evolving plan for keeping him engaged in the genealogy work he loves.

“It’s hard to care for people with multiple chronic conditions without knowing what’s most important to them,” says Dr. Ralston. “We’re making progress. Now that we have these domains, our work is to connect them to care options that support a patient’s personal values.”

by Dona Cutsogeorge

KPWHRI News

November 2017

- Patients may not be telling their doctors what matters to them most

- Meditating: Easier and more beneficial than you think

- And when I’m 84?

- How to keep guns — and troubled teens — safe

- Video: Moving to Health

- SIRC 4th Biennial Conference: We opened Pandora’s Box of implementation questions