Aging with an edge: The ACT study advances genetics and brain science

What if scientists could combine the latest in genetics and brain science with decades of rich data from research and clinical visits? That interdisciplinary cross-fertilization is just what’s happening with Adult Changes in Thought (ACT), a joint Group Health-University of Washington (UW) study funded by the National Institute on Aging. After decades of studying Group Health seniors to pinpoint risk factors for conditions including dementia, ACT researchers are now collaborating with new partners to learn even more.

“This basic science has a different ‘flavor’ than most Group Health research,” said ACT principal investigator Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, vice president for research at Group Health and Group Health Research Institute (GHRI)’s executive director. “We’re excited to be taking ACT to a new level—and contributing to major studies of the genetics and brain science of dementia, nationally and internationally.”

Strength in numbers

“Many scientific partners are intrigued by all we have to offer, including detailed information, precise diagnosis, and biostatistical and programming knowhow,” said the study’s UW principal investigator, Paul K. Crane, MD, MPH, a UW School of Medicine associate professor of medicine and GHRI affiliate investigator.

A lot of carefully collected information is needed to maximize diversity and statistical power to distinguish random events from what really causes disease. But there is strength in numbers. Just as ACT participants contribute to something larger than themselves, the study has joined many collaborations to do high-value, efficient research. With the Allen Institute for Brain Science, ACT is helping to investigate lasting effects of traumatic brain injuries (TBI). ACT is contributing brain tissue from more than 200 participant autopsies that show which genes were being expressed as proteins. “No one has ever had a chance before to look at whether people who’ve had head injuries had different gene expression in their brains,” Dr. Crane said.

In July, at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Copenhagen, ACT researchers will present information about how the brain may still be affected long after a head injury has happened.

Group Health is moving toward changing ACT consent so participants can choose to be informed about their own genetics. The study has already helped make major discoveries through collaborating in various genetic consortia:

- The national Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) network is showing how best to combine information from genetics and electronic health records—and has identified some genes for diseases, including thyroid disease.

- ACT is the single largest study in the Alzheimer’s Disease Sequencing Project (ADSP), which is sequencing people’s whole exomes (the ~3 percent of the genome that gives instructions for all the body’s proteins) to search for small variations that are more common in people with Alzheimer’s disease than in those without it.

- The Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC) has found some new genes involved in Alzheimer’s disease—and how the genetics of the disease differs in African Americans versus whites. “We’re really proud that all of our efforts to enroll a population that reflects the diversity of the Seattle area paid off in contributing to this important work,” Dr. Crane said.

- And in the largest-ever study of Alzheimer’s disease, the International Genetics of Alzheimer’s Project (IGAP) helped identify new genes involved in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

Building on history

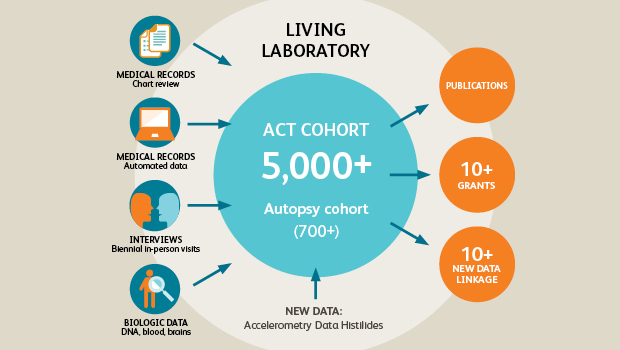

For 20 years, the longitudinal ACT study has been thoroughly tracking what happens with a cohort of randomly selected Group Health patients older than 65 as they lead their lives. To be invited to enroll, people must be free from cognitive impairment (problems with memory and thinking). Over time, some develop dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, and some die—and new participants join and keep the study number steady at 2,000. The study has become a “living laboratory” to understand the aging process—particularly in the brain—and to identify risk factors for conditions including dementia.

Every two years, ACT participants visit the GHRI Research Clinic—or staff make home visits—to assess their thinking and physical health. ACT combines information from these research visits with comprehensive medical and pharmacy records. Over the years, this work has produced many useful insights for clinicians and public health—and practical healthy-aging tips that people can put to immediate use in their everyday lives: from exercising regularly and controlling blood sugar levels to wearing shoes indoors to help prevent falling.

ACT has collected participants’ DNA for many years—and asked them whether they would allow an autopsy on their brains after their death. With more than 500 such brains, this has grown into a unique brain bank: the only population-based study involving autopsy and study of diseases of nervous system tissue, according to Thomas J. Montine, MD, PhD, the UW pathology chair. His leadership helped launch this work, and he now leads the UW’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC), in which some ACT patients participate.

Gratitude

“Thanks to our participants, we already have a tremendous database with unparalleled depth and density of information,” Dr. Crane said. “We can evaluate a wide range of exposures and brain outcomes for decades to come.”

“Our participants’ completeness of follow-up is an amazing 98 percent, and some have been with us since the study started,” Dr. Larson said. “We’re grateful for their efforts and the exquisite information about the history of their lives that contributes to all we’re learning about aging and the brain. We couldn’t do any of this work without the dedication of our wonderful participants and staff.”

ACT study

ACT study: Long-running study of aging examines changes in Group Health patients over time

Drs. Larson and Crane co-lead Group Health-University of Washington collaboration learning how to promote healthy aging.